(Bloomberg) — Profits and losses are not usually seen as a consideration for central banks, but the rapidly growing red ink at the Federal Reserve and many peers risk becoming little more than an accounting oddity.

Most Read From Bloomberg

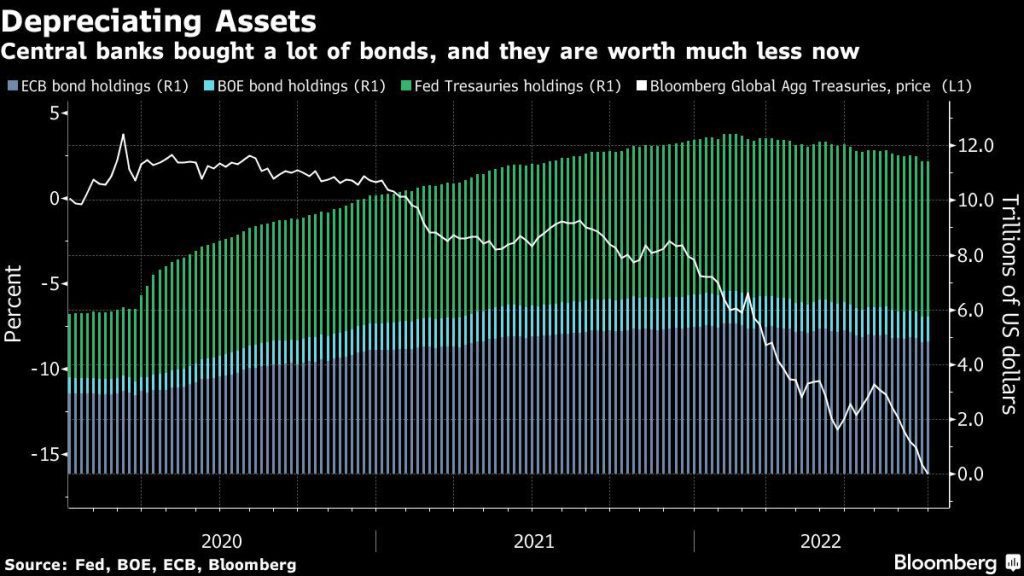

The bond market is suffering its worst sell-off in a generation, as a result of high inflation and sharp interest rate increases implemented by central banks. Falling bond prices, in turn, mean paper losses on massive holdings that the Federal Reserve and others have accumulated during bailout efforts in recent years.

Increasing interest rates also involves central banks paying more interest on the reserves that commercial banks place with them. This drove the Fed into operating losses, creating a gap that may eventually require the Treasury to fill it through debt sales. The British Treasury is already preparing to make up for the loss in the Bank of England.

The British move highlights a fundamental shift in countries including the United States, where central banks are no longer a significant contributor to government revenue. The US Treasury will see an “amazing swing,” from receiving about $100 billion last year from the Federal Reserve to a potential annual loss rate of $80 billion by the end of the year, according to Amherst Pierpont Securities LLC.

Accounting losses threaten to fuel criticism of the asset-buying programs undertaken to rescue markets and economies, most recently when Covid-19 shut down large sections of the global economy in 2020. Combined with the current outbreak of inflation, this could spur calls to rein in the independence of monetary policymakers. or limiting the steps they can take in the next crisis.

said Jerome Hegele, chief economist at Swiss Re, who previously worked for Switzerland’s central bank.

The following figures show the range of operating losses or balance sheet losses that are now realized:

-

The Fed’s transfers to the US Treasury were negative $5.3 billion as of October 19 – a sharp contrast to the positive numbers seen recently at the end of August. The negative number amounts to the IOU which will be repaid with any future income.

-

The Reserve Bank of Australia posted an accounting loss of A$36.7 billion ($23 billion) for the 12 months to June, putting it in negative A$12.4 billion.

-

Dutch central bank governor Klaas Knott warned last month that he expects cumulative losses of around 9 billion euros ($8.8 billion) for the coming years.

-

The Swiss National Bank reported a loss of 95.2 billion francs ($95 billion) for the first six months of the year as the value of its foreign currency holdings plummeted – the worst performance in the first half since its founding in 1907.

While for a developing country, losses in the central bank can undermine confidence and contribute to a mass exodus of capital, this type of credibility challenge is not likely for a rich country.

As Seth Carpenter, Morgan Stanley’s chief global economist and former US Treasury official, said: “The losses have no material impact on their ability to manage monetary policy in the near term.”

“We don’t think we’ve been affected at all by our ability to act,” Michael Bullock, Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, said in response to a question last month about the RBA’s negative equity position. After all, “We can create money. That’s what we did when we bought bonds.”

But there could still be consequences. Central banks have already become politically charged institutions after failing, by their own admission, to anticipate and act quickly against emerging inflation over the past year or more. Incurring losses adds another attraction to cash.

Implications for the European Central Bank

For the European Central Bank, the potential for mounting losses comes after years of buying government bonds despite the reservations of conservative officials who argue they have blurred the lines between monetary and fiscal policy.

With inflation soaring to five times the ECB’s target, pressure is mounting to dump bond holdings – a process called quantitative tightening for which the ECB is currently preparing even as the economic outlook darkens.

“While there are no clear economic constraints on ongoing central bank losses, there is a potential for these to become political constraints on the ECB,” Goldman Sachs Group economists George Cole and Simon Fresenet said. Especially in northern Europe, it “might fuel discussion of quantitative tightening.”

President Christine Lagarde gave no indication that the ECB’s QT decision would be driven by the possibility of losses. She told lawmakers in Brussels last month that making profits was not part of the central banks’ job, and insisted that fighting inflation remains the “sole objective” of policymakers.

Bank of Japan, Federal Reserve

The Bank of Japan remains separate for the time being, as it did not raise interest rates and is still charging a negative rate on a portion of banks’ reserves. But things could change when Governor Haruhiko Kuroda steps down in April, and his successor faces historically high inflation.

As for the Fed, Republicans in the past have expressed opposition to its practice of paying interest on excess bank reserves. Congress granted that power back in 2008 to help the Fed control interest rates. With the Fed now incurring losses, and Republicans likely to control at least one chamber of Congress in the November midterm elections, the debate may resurface.

The Fed’s turnaround could be particularly notable. After paying up to $100 billion to the Treasury in 2021, it could face losses of more than $80 billion year-over-year if policymakers raise interest rates by 75 basis points in November and 50 basis points in December – as markets expect – Stephen Stanley estimates , chief economist at Amherst Pierpont.

Without the income from the Federal Reserve, the Treasury then needs to sell more debt to the public to fund government spending.

“This may be too vague to hit the public radar, but a populist can spin the story in a way that doesn’t reflect well on the Federal Reserve,” Stanley wrote in a note to clients this month.

– With the help of Garfield Reynolds.

(Adds a reference to the Bank of Japan after the subtitle “BOJ, Fed.”)

Most Read From Bloomberg Businessweek

© Bloomberg LP 2022

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

Dow Jones Futures: Microsoft, MetaEngs Outperform; Robinhood Dives, Cryptocurrency Plays Slip

Strategist explains why investors should buy Mag 7 ‘now’

Everyone gave Reddit an upvote