If you have ever watched predatorI noticed the tactical advantage that his thermal vision gave the alien warrior. In fact, even with the strong camouflage, Dutch and his team ended up in a big pickle.

However, in reality, it seems that it may be the prey that has the ability to sense in the infrared spectrum. And research has now revealed that this unique ability may be entirely man-made. To the hair on the back of some of the smallest mammals.

Not with my back hair-back-back

Small mammals, such as shrews and rodents, have fur that combines multiple types of hair into a thick, protective layer. The fur should keep the animal warm, relatively dry, and protect it from the elements. But what if it could also protect against predators? Nestled among this fur are special “guard hairs” that researchers now believe act as tiny infrared sensors.

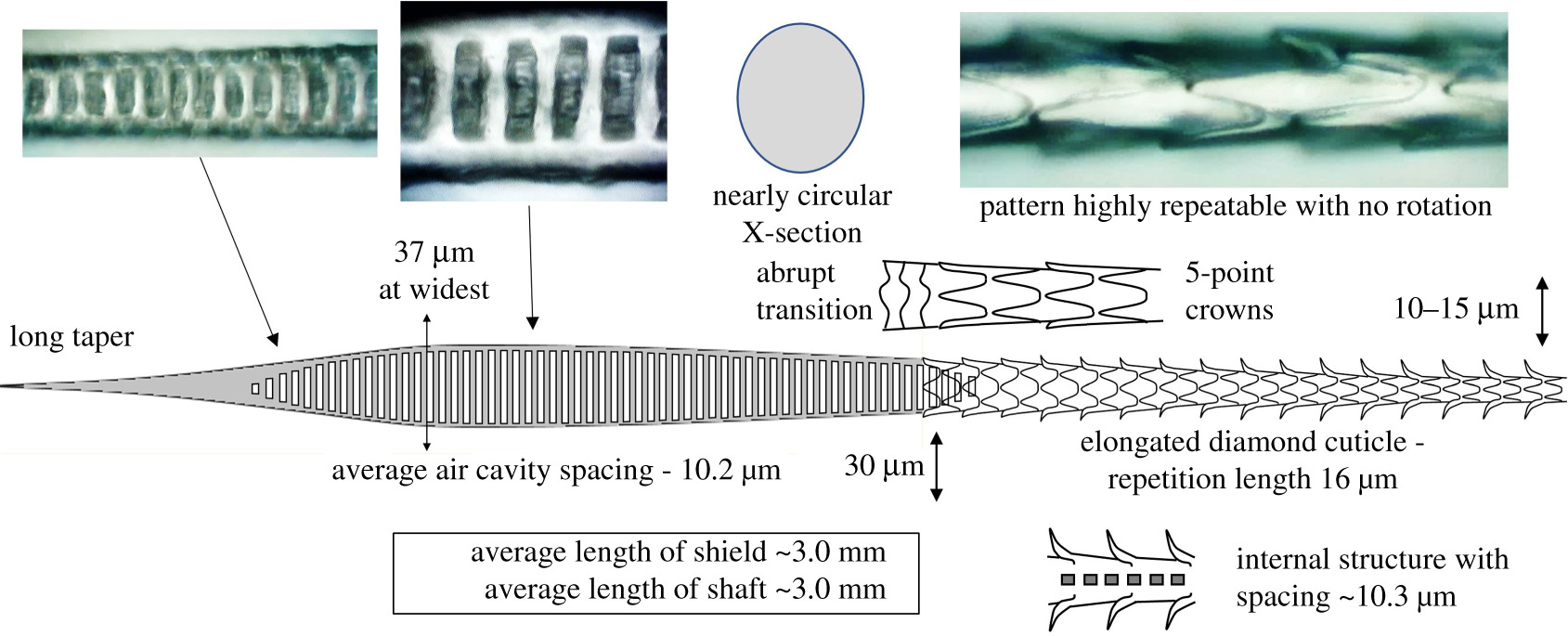

Guard hairs make up 1% to 3% of the fur. The hairs usually stand straight out, and stand out somewhat from the rest of the fur. Guard hairs also tend to display a somewhat distinctive striped pattern not seen in other types of mammalian hair.

For years, scientists have been puzzled by the periodic band patterns observed in the protective hairs of small mammals. These hairs show internal bands spaced 6 to 12 micrometers apart. If you’ve been staring at an electromagnetic spectrum chart lately, you might realize that they closely match infrared wavelengths. This suggests an unrecognized function—the ability to sense infrared light, perhaps. In fact, these wavelengths cover the same part of the infrared spectrum used by heat-seeking missiles and thermal imaging devices.

This feature had obvious survival benefits for nocturnal animals and heavy predators. It could give a small creature the ability to detect warm sources of heat—such as predators—approaching from behind. No need to keep your eyes on the back of your head, or look over your shoulder forever. If your thermal senses picked up something warm approaching from behind, it could be worth making a lunge.

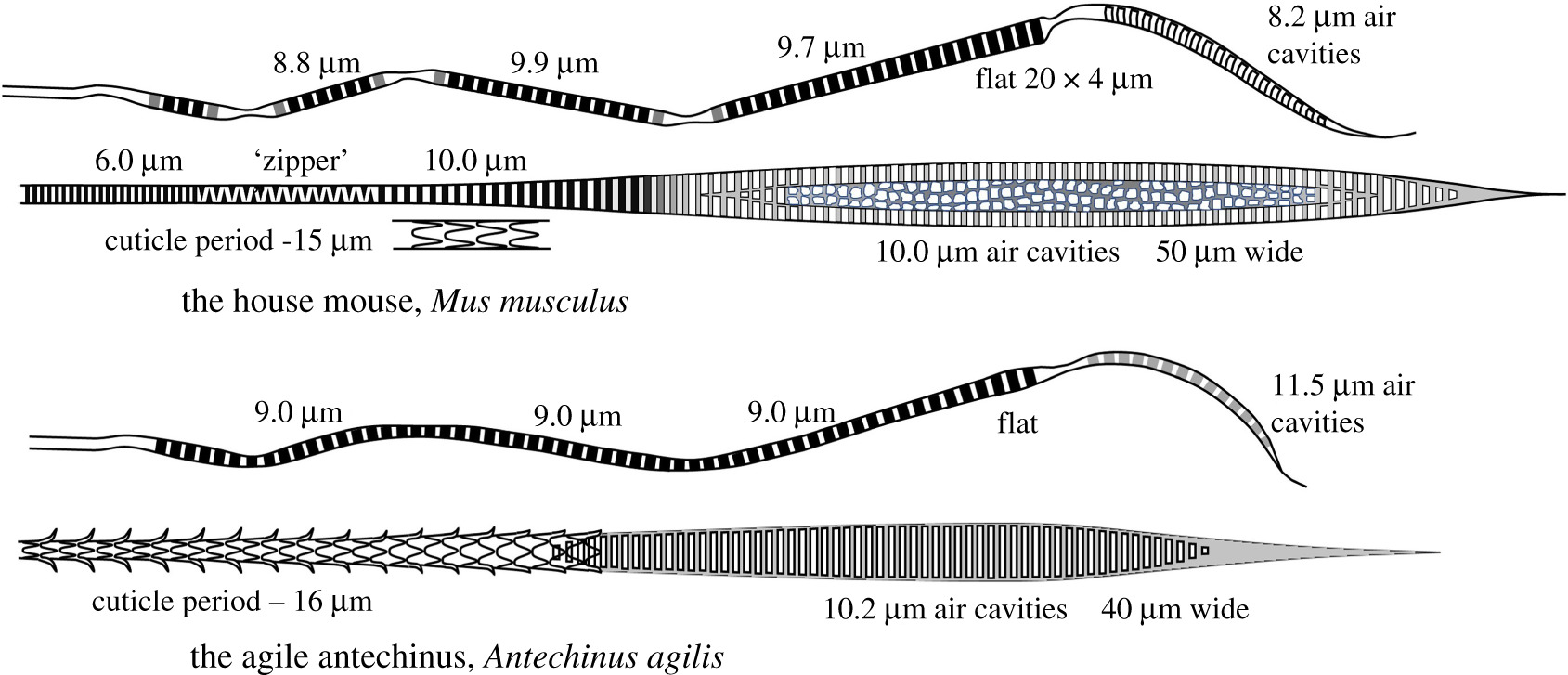

Researchers have focused their research on guard hairs on three types: Muscle, muscleHe is a house mouse. Anchinus Agelis, A mouse-like marsupial, and Sorx Araneusthe common shrew. Despite the many differences between species, the guard hairs share some similarities. Their results showed that despite evolutionary differences spanning millions and millions of years, these species share very similar microscopic hair structures that appear to be tuned to wavelengths between 8-12 micrometers—ideal for thermal imaging.

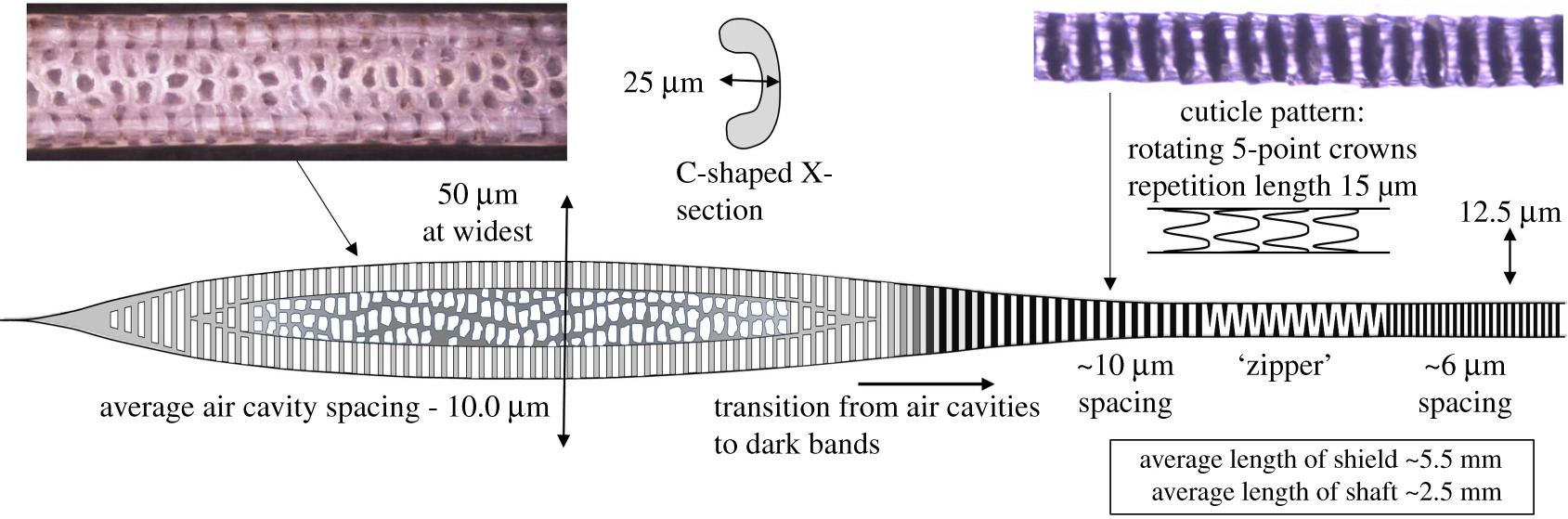

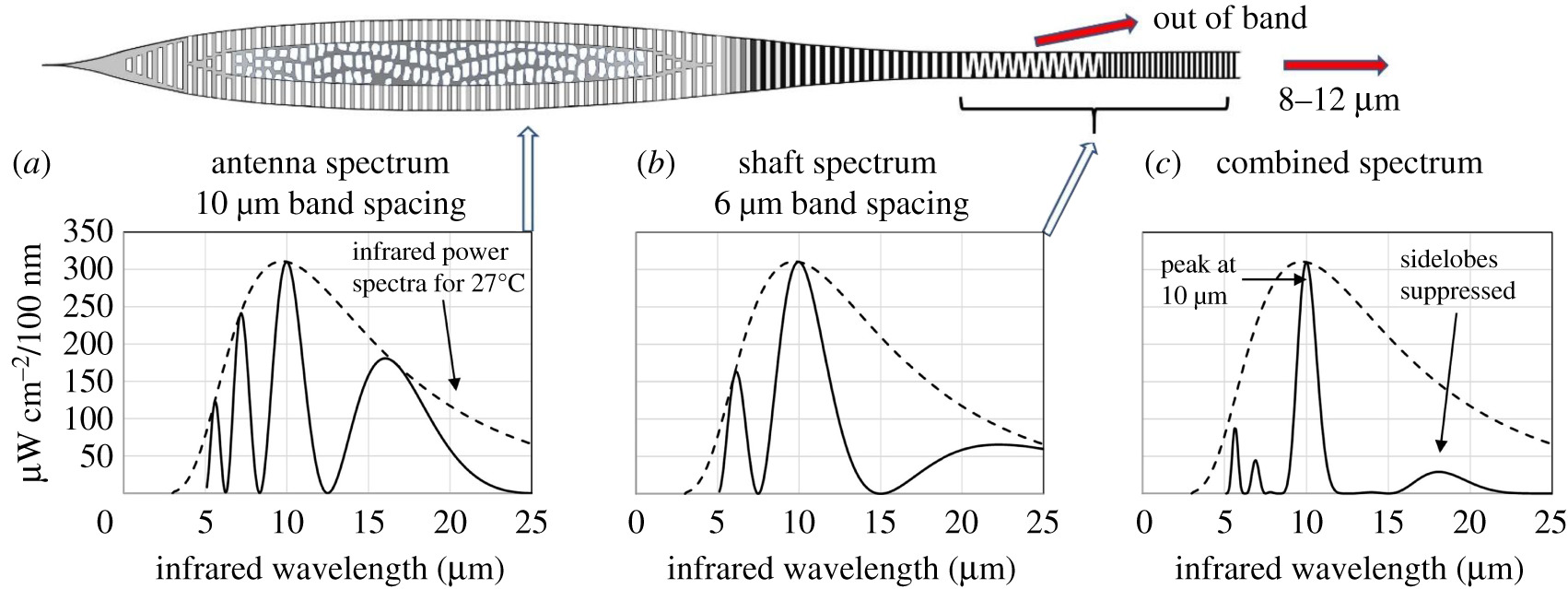

Taking the house mouse as a prime example, the hairs have a sophisticated structure. The wider sections of the guard hairs, referred to as the “shield”, are thought to act as infrared absorbers. They contain two tubes connected by a membrane, with air cavities spaced at periodic intervals of about 10 micrometres. Towards the base of the shield region, the hair narrows, and instead of air cavities, the hair features distinct dark bands at similar intervals. The narrow sections are thought to help focus the absorbed infrared energy at the base of the hair. This is followed by a relatively variable “zipper” section, with dark hemispheres arranged around the hair shaft. This is thought to act as a “spectral filter” that radiates wavelengths outside the 8–12 micrometre range. Calculations suggest that the zipper filter means that infrared energy in this critical wavelength range makes up 72% of the “signal” reaching the base of the hair, rather than just 33% otherwise. The last section of the column contains finer bands, only 6 μm apart.

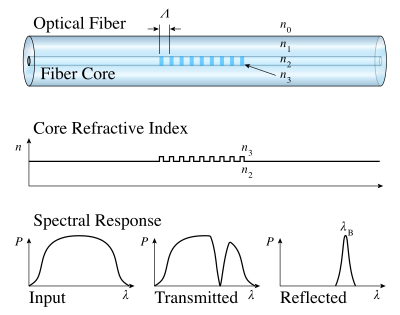

The whiskers are thought to work similarly to infrared antennas, with their rigid, straight lines and periodic stripes acting as heat detectors. The stripes themselves appear to be made of infrared-transparent biological material with varying refractive indices. The researchers liken this to a man-made device called a fiber Bragg grating, or FBG. This device uses the periodic variation in the refractive index of optical fibers to create a filter for a particular wavelength. The protective whiskers could use a biological version of the same mechanism to filter out the infrared wavelength of interest.

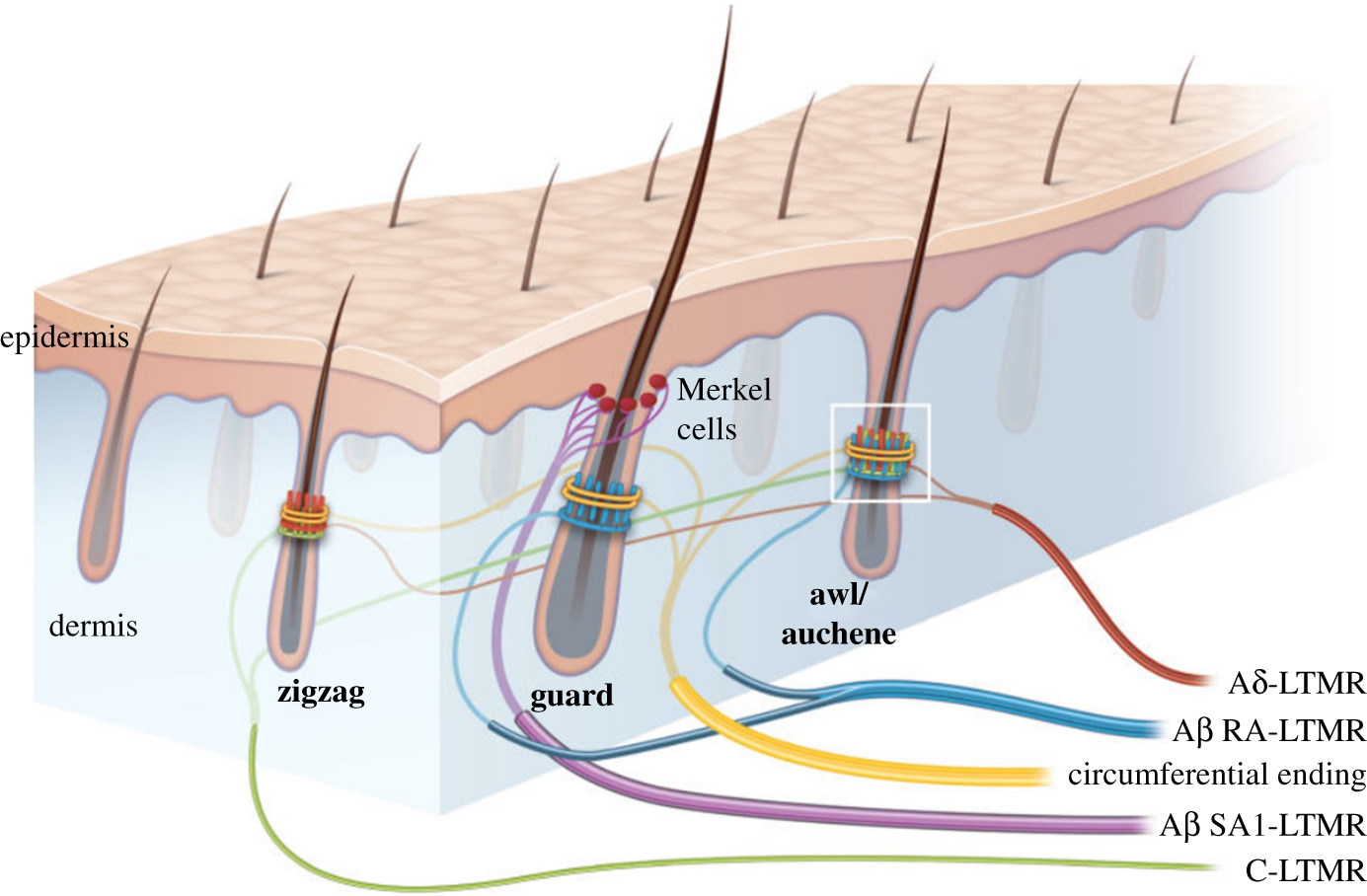

Meanwhile, the animal needs to pick up the signal from a type of sensor cell at the base of the hair. In fact, the researchers found that the house mouse does have Merkel cells uniquely located at the base of the guard hairs, which are arranged around the mouse’s torso. It’s thought that these cells may be responsible for sensing infrared light, since the hairs themselves act as antennas to focus infrared energy onto them.

The researchers also expanded on whether predators have adapted to this as well. Notably, they found that cold-blooded snakes were nearly invisible in the infrared thermal range. Similarly, cats have relatively low frontal heat emissions. Both therefore have an advantage in hunting against mammals with a heat-sensing defense mechanism. In fact, these creatures are particularly adept at hunting mice and other small mammals, as you might expect!

The research is still in its early stages. More work remains to be done to confirm the true purpose of these guard hairs. Regardless, their intricate microstructures provide compelling evidence that they do indeed function as antennae to capture infrared radiation for sensory purposes.

The discovery of these natural infrared sensors is not just a biological curiosity. It could also be useful in the field of photonics. The ability of guard hairs to act as tiny infrared antennas could inspire new optical devices, or improve existing technologies.

In addition, this research may have implications for evolutionary biology, providing new insights into the ancient origins of hair in mammals and marsupials. The resilience of guard hairs over millions of years suggests that they played a crucial role in the survival of early mammals, perhaps dating back to the Triassic.

Some small mammals, however, have always been able to evade predators that sneak up on them. And now we may be getting a secret insight into this little trick. Maybe it wasn’t their eyes or their keen sense of vibrations, but a hidden thermal sense that had been lurking in their fur all along.

Featured Image: “Laboratory mouse mg 3263” by [Rama]

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

Scientists confirm that monkeys do not have time to write Shakespeare: ScienceAlert

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova