Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter. Explore the universe with news about amazing discoveries, scientific advances, and more..

CNN

—

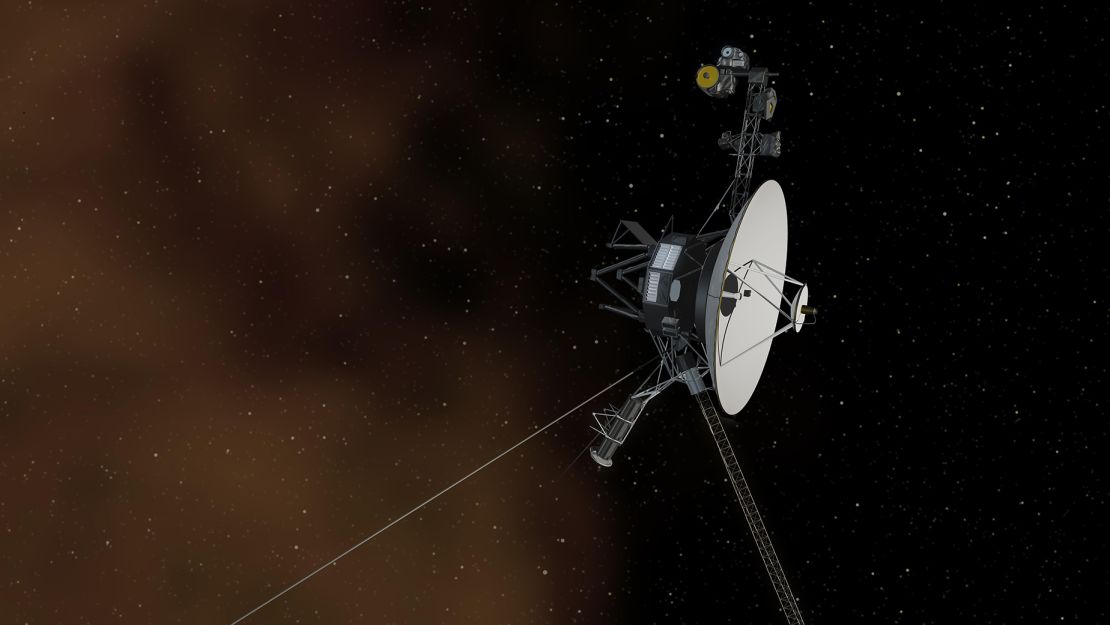

NASA engineers have successfully fired up a set of thrusters that the Voyager 1 spacecraft has not used in decades, solving a problem that could prevent the 47-year-old spacecraft from communicating with Earth billions of miles away.

When Voyager 1 launched into space on September 5, 1977, no one expected the probe to still be operating today.

Because of its exceptionally long mission, Voyager 1 faces problems as its parts age in the cold outer reaches of our solar system. When problems arise, engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, have to be creative while also being careful about how the spacecraft reacts to any changes.

Voyager 1 is currently the farthest spacecraft from Earth, about 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away. The spacecraft operates outside the heliosphere—the Sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends far beyond the orbit of Pluto—where its instruments are taking direct samples of interstellar space.

Earlier this year, engineers discovered a problem when a fuel tube inside one of Voyager’s thrusters became clogged. If the thrusters are clogged, they can’t generate enough force to keep the spacecraft stable. Voyager’s thrusters keep the spacecraft in an orientation that allows it to communicate with Earth.

If Voyager 1 wasn’t positioned so that its antenna was pointed toward Earth, the spacecraft wouldn’t be able to “hear” commands from control or send data, according to Calla Cofield, a media relations specialist at JPL.

“If the motors that keep the antenna pointed at Earth get clogged, that would be the end of the mission,” she said.

The team realized they would have to send commands to the spacecraft to switch to another set of engines, but the solution would not be simple.

This isn’t the first time Voyager 1 has needed to switch to another set of thrusters in recent decades. Fortunately, the spacecraft has three sets of thrusters: two sets of thrusters for thrust and one set for course correction maneuvers.

Voyager 1 used thrusters for a variety of purposes during its flybys of planets such as Jupiter and Saturn in 1979 and 1980, respectively.

Now, the spacecraft is on a steady path away from our solar system, so it only needs one set of thrusters to help keep its antenna pointed toward Earth. To fuel the thrusters, liquid hydrazine is converted to a gas and released in about 40 short puffs each day to keep Voyager 1 pointed correctly.

Over time, engineers discovered that the fuel tube inside the thrusters could become clogged with silicon dioxide, a byproduct of the aging of the rubber membrane in the fuel tank. As the thrusters clogged, they generated less power.

In 2002, the team ordered Voyager 1 to switch to the second set of thrusters when the first set showed signs of clogging. Engineers switched back to the thrusters in 2018 when the second set also showed signs of clogging.

But when the team recently checked the condition of Voyager’s trajectory correction engines, they were more clogged than the previous two sets of engines.

When the team first turned Voyager on to the course-correction engines six years ago, the tube opening was 0.01 inches (0.25 millimeters) wide. But now, the blockage has shrunk it to 0.0015 inches (0.035 millimeters) — half the width of a human hair, according to NASA.

It’s time to go back to another set of position-specific drivetrains.

As Voyager 1 and its twin Voyager 2 spacecraft aged, the mission team slowly shut down non-essential systems on both spacecraft to conserve energy, including the heaters. As a result, Voyager 1’s components were now getting colder, and the team knew they couldn’t simply send a command to Voyager 1 to immediately switch to one of its one-way thrusters without doing something to warm them up.

But Voyager 1 doesn’t have enough power to turn any heaters back on without turning something else off, and its science instruments are too valuable to turn off if they don’t turn back on, the team said.

After going back to the drawing board, the team realized that it would be possible to turn off one of the spacecraft’s main heaters for about an hour, which would allow engineers to safely turn on the thruster heaters and make the switch.

The plan worked, and by August 27, Voyager 1 was back to relying on one of its original propulsion systems to stay in contact with Earth.

The team has taken steps to use the thrusters less, and expects to get another two or three years out of the original set, said Todd Barber, Voyager’s propulsion engineer.

Once the spacecraft exhausts this set of thrusters, Voyager 1’s remaining option is the other, already clogged, thruster set.

“All the decisions we have to make in the future will require much more analysis and caution than they have in the past,” Susan Dodd, Voyager project manager, said in a statement.

Voyager 2 also underwent thrust swaps in 1999 and 2019, and “the situation there is less severe,” Barber said. Voyager 2 has traveled more than 12 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) from Earth.

The information these long-lived probes collect helps scientists learn about the shape of the comet-like heliosphere and how it protects Earth from energetic particles and radiation in interstellar space.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again