Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

—

When a supernova was seen shining in the night sky for six months in 1181, it was so bright that Chinese and Japanese astronomers recorded it as a “guest star” in the constellation Cassiopeia.

Now, astronomers using the Keck Cosmic Web Imager, or KCWI, at the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, have mapped a field of strange filaments extending far from where the star exploded.

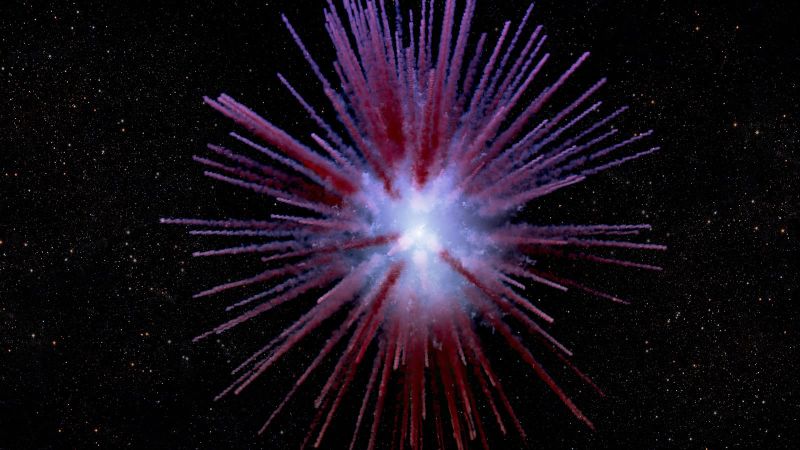

This is the first time that the soft, dandelion-like filaments have been observed in 3D as they flow away from the site of the explosion around the dead star. The researchers shared the results of their work, which provide new clarity about the structure of the supernova remnant, in a paper published on October 24. Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“A standard image of a supernova remnant would be a still image of a fireworks display,” study co-author Christopher Martin, a professor of physics at Caltech and leader of the team that built the imager, said in a statement.

“KCWI gives us something like a ‘movie’ where we can measure the movement of the embers from the explosion as they emerge from the central eruption.”

This discovery adds another piece to the puzzle as astronomers seek to understand the remnants this unusual supernova left behind. In this case, the filaments radiate away from the “zombie star” created by the explosion. Every time researchers observe a supernova, they discover more surprises.

The search for visual evidence of the supernova, called SN 1181, continued for centuries before amateur astronomer Dana Bachek first discovered its remnant in 2013.

Bachek discovered a nebula near the original site of the supernova while examining images taken by NASA’s now-retired Wide Field Infrared Survey mission. Albert Zijlstra, professor of astrophysics at the University of Manchester in England, later submitted The relationship between the nebula and SN 1181 In 2021.

The nebula, a cloud of material ejected from a supernova, is named Pa 30.

Then, in 2023, astronomers spotted strange filaments glowing with sulfur light inside the nebula. Scientists know that the supernova created the strings, but it is unclear how and when these structures formed.

The supernova of 1181 was no ordinary star explosion. Scientists believe that this event resulted from a thermonuclear explosion that occurred on a white dwarf, or a dense dead star. Two white dwarf stars may have collided to form a supernova. But the impact created only a partial explosion.

Violent supernova explosions usually destroy white dwarfs, but the partial explosion, known as a rare-type supernova, left behind a zombie star instead.

“Because this was a failed explosion, it was fainter than normal supernovas, which has been shown to be consistent with historical records,” study co-author Ilaria Caiazzo, an assistant professor at the Institute of Science and Technology in Austria, said in a statement.

To get a closer look at the filaments left behind by the strange explosion, astronomers turned to the Keck cosmic web imager. The tool is designed to capture information for each pixel in an image across multiple wavelengths of light.

The powerful data captured by the tool allowed the team to measure the movements of each thread and create a 3D map. While filaments moving toward Earth are in the bluest, high-energy part of visible light that the human eye can see, filaments moving in the opposite direction appear redder.

It is similar to the Doppler effect observed when emergency vehicles turn on their sirens; An approaching car’s horn will sound at a higher frequency, but as you move away, the sound waves expand and emit a lower frequency.

The Keck Cosmic Web Imager allowed measurements of the speed of any material within the nebula that was emitting light. When the team analyzed the data, they found that the filaments were flying away from the supernova site at a speed of 2.2 million miles per hour (about 1,000 kilometers per second).

“We found that the material in the filaments is expanding ballistically,” said Tim Cunningham, the study’s lead author and a NASA Hubble Fellow in the Center for Astrophysics. Harvard and Smithsonian, in a statement. “This means that the material has not been slowed down or accelerated since the explosion. From the measured velocities, and looking back in time, you can roughly pinpoint the explosion in the year 1181.”

Although the light of the supernova first reached Earth on August 6, 1181, the explosion occurred much earlier. The star was 7,500 light-years from Earth, so it took 7,500 years for the bright light from the supernova to become visible in Earth’s night sky, said Zijlstra, who was not involved in the new study.

The 3D data also pointed to new mysteries such as a large cavity within the nebula’s structure as well as evidence that the supernova occurred asymmetrically.

The filaments appear to radiate from an outer shell extending from the central star, Cunningham said. But the team is still unsure how the filaments form in the first place.

“There are two proposed scenarios: 1) a shock wave moving back toward the star causes the dust to sublimate into hot gas, which then cools quickly and collects into straight filaments or 2) clumps of dust are stripped away by the fast winds of the central star,” Cunningham said in an email. . “Our observations are not able to distinguish between these two models, and more observations and theories are needed to understand this nebula, but our observations provided an important piece of the puzzle!”

Studies were conducted last year to shed light on the secrets of the threads after a research paper revealed them in 2023.

While the linear filaments are unusual for a supernova, Zijlstra said they resemble features seen in planetary nebulae, or the glowing envelopes of gas around dying stars, such as planetary nebulae. The Southern Ring Nebula and Ring nebula Observed by the James Webb Space Telescope.

The unique structure of the filaments “represented a major challenge to explain physically — especially given that the (previously) observed filaments seemed to extend from the central to the outer regions,” said Takatoshi Ko, a doctoral student at Harvard’s Center for Early Universe Research. University of Tokyo.

Kuo was not involved in the new Keck Cosmic Web Imager observations, but he and his colleagues were published a study Earlier this year, it was suggested that the supernova remnant consists of multiple regions, making it difficult to reconcile the exact composition of the filaments.

Observations from the new study show that the filaments only extend across the outer regions of the nebula, rather than from the center outward, adding further evidence to the idea that there are multiple regions within the supernova remnant, Kuo said. The more clarity researchers get about the structure of the filaments, the more likely they are to discover what formed the cosmic dandelion in the first place.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again

NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer is preparing to reveal hidden ice reserves on the Moon