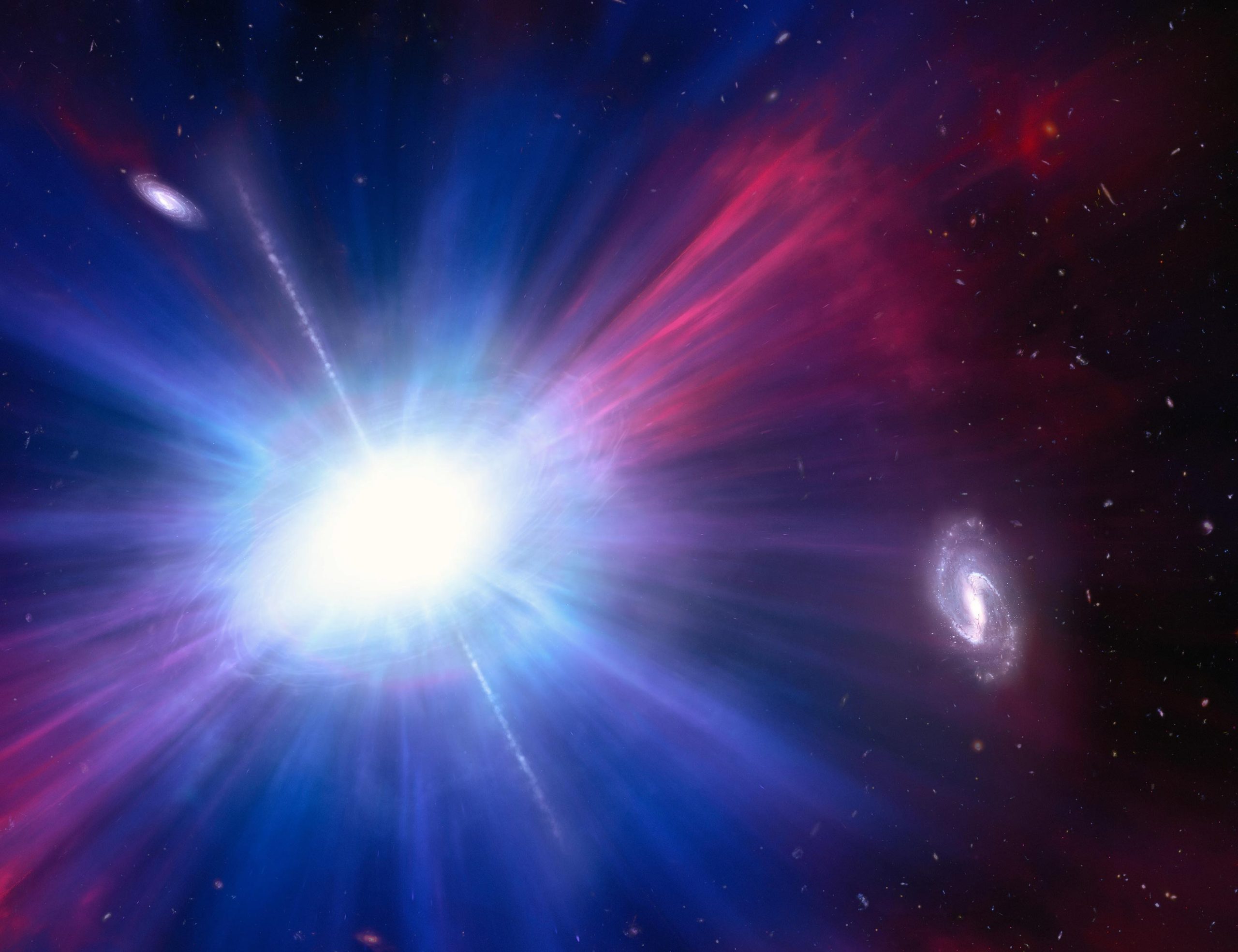

This is an artist’s conception of one of the brightest explosions ever seen in space. Called the Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transient (LFBOT), it shines intensely in blue light and develops rapidly, reaching peak brightness and fading again within days, unlike supernovae that take weeks or months to dim. Only a few previous LFBOTs have been discovered since 2018. They all occur within galaxies where stars are born. But this illustration shows that Hubble discovered that the LFBOT flash seen in 2023 occurred intergalactically. This only exacerbates the mystery of what these fleeting events are. Because astronomers do not know the basic process behind LFBOTs, the explosion shown here is purely speculative based on some known transient phenomena. Image credit: NASA, ESA, NSF’s NOIRLab, Mark Garlick, Mehdi Zamani

Detecting extremely bright light explosions between galaxies

A clear, starry night is deceptively quiet for backyard skywatchers. In fact, the sky is ablaze with things that explode in the night, like photographers’ cameras shooting out. Most of these flashes are stellar explosions or collisions. They are so faint that they can only be captured by the endless eyes of telescopes that constantly monitor the night sky for such transients.

Among the rarest of these random cosmic events is a small class called Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients (LFBOTs). They shine intensely in blue light and evolve rapidly, reaching peak brightness and fading again within days, unlike supernovae that take weeks or months to dim.

The first LFBOT was found in 2018. Nowadays, they are captured once a year, and thus only a few are known. There are several theories behind the causes of powerful explosions. But Hubble came and made this phenomenon even more mysterious.

One LFBOT appeared in 2023 in a place no one expected, far between two galaxies. Only Hubble can pinpoint its surprising location precisely. If very strong supernova flavor causes LFBOTs, they should explode in the spiral arms of galaxies where star birth takes place. Massive newborn stars do not live behind supernovas long enough to wander beyond their nesting grounds within the galaxy.

Astronomers agree that more LFBOTs need to be discovered so theorists can better characterize clusters of these elusive transient events.

Hubble Space Telescope image of a fast luminous blue optical transient (LFBOT) identified as AT2023fhn, marked with indicators. It shines intensely in blue light and evolves rapidly, reaching peak brightness and fading out again within days, unlike supernovae that take weeks or months to dim. Only a few previous LFBOTs have been discovered since 2018. The surprise is that this latest transit, seen in 2023, is located at a significant offset from both the barred spiral galaxy on the right and the dwarf galaxy on the upper left. Only Hubble can determine its location. The results leave astronomers even more puzzled because all previous LFBOTs were found in star-forming regions in the spiral arms of galaxies. It is not clear what astronomical event might trigger such an extragalactic explosion. Image credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Ashley Chrimes (ESA-ESTEC/Radboud University)

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope finds a strange explosion in an unexpected place

A very rare and strange burst of unusually bright light in the universe just got weirder – thanks to the Eagle Eye NASA‘s Hubble Space Telescope.

The phenomenon, called Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transient (LFBOT), has appeared on the scene where it was not expected to be found, far away from any host galaxy. Only Hubble can determine its location. The results leave astronomers even more puzzled. First of all, they don’t know what LFBOTs are. The Hubble results suggest they know less by ruling out some potential theories.

LFBOTs are among the brightest known visible-light events in the universe, exploding as unexpectedly as camera lights. Only a handful have been found Since the first discovery in 2018 – An event located about 200 million light-years away, nicknamed “The Cow.” At present, LFBOTs are unveiled once a year.

Recent results and observations

After its initial discovery, the latest LFBOT was observed by multiple telescopes across the electromagnetic spectrum, from X-rays to radio waves. The temporary event designated AT2023fhn and nicknamed “The Finch” showcased all the hallmarks of LFBOT. It shined intensely in blue light and evolved rapidly, reaching peak brightness and fading again within days, unlike supernovae, which take weeks or months to dim.

But unlike any other LFBOT seen before, Hubble found that Finch is located between two neighboring galaxies — about 50,000 light-years from a nearby spiral galaxy and about 15,000 light-years from a smaller galaxy.

The image titled “AT2023fhn HST WFC3/UVIS” with color key, scale bar and compass arrows shows three galaxies against the velvety black space background. The largest is the blue-white spiral galaxy in the center of the image. Two small galaxies are white spots towards the left. There is a strange white spot with red indicators near the top of the image, which is a bright glow from an unknown object that exploded, but is not associated with any galaxies. Image credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Ashley Chrimes (ESA-ESTEC/Radboud University)

“The Hubble observations were the really crucial thing. They made us realize that this was unusual compared to other similar things, because without the Hubble data we wouldn’t have known,” said Ashley Krems, lead author of the Hubble paper who published the discovery in an upcoming issue of the journal Hubble. . Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). He is also a European Space Agency Research Fellow, formerly at Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands.

While these massive explosions are presumed to be a rare type of supernova called collapse supernova, giant stars that go supernova are short-lived by stellar standards. Therefore, massive progenitor stars do not have enough time to travel far from their birthplace – a group of newborn stars – before exploding. All previous LFBOTs have been found in the spiral arms of galaxies where star birth occurs, but Finch is not present in any galaxy.

“The more we learn about LFBOTs, the more they surprise us,” Krems says. “We have now shown that LFBOTs can occur at a long distance from the center of the nearest galaxy, and the Finch location is not what we would expect for any type of supernova.”

Initial alerts and additional confirmations

The Zwicky Transient Facility — a ground-based ultra-wide-angle camera that scans the entire northern sky every two days — first alerted astronomers to Finch on April 10, 2023. Once it was spotted, researchers launched a pre-planned program for Finch. Notes that were on their toes, ready to quickly turn their attention to any potential LFBOT candidates that might emerge.

Spectroscopic measurements made with the Gemini South telescope in Chile found the goldfinch to have a scorching temperature of 36,000 degrees. F. Gemini also helped determine its distance from Earth so its luminosity could be calculated. Combined with data from other observatories including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array Radio Telescopes, these results confirmed that the explosion was indeed an LFBOT.

Possible explanations and future research

One theory suggests that LFBOTs may result from being devoured by stars of intermediate mass Black hole (Between 100 to 1000 solar masses). NASA James Webb Space TelescopeThe high resolution and infrared sensitivity could eventually be used to find that Finch exploded inside a globular star cluster in the outer halo of one of two nearby galaxies. A globular star cluster is the most likely place to find an intermediate-mass black hole.

To explain Finch’s unusual location, researchers are considering the possibility that it is the result of a collision between two neutron stars, traveling far beyond their host galaxy, and have been heading toward each other for billions of years. Such collisions produce a kilonova, an explosion 1,000 times more powerful than a standard supernova. However, there is a speculative theory that if one of the neutron stars were highly magnetized – a magnetar – it could greatly amplify the force of the explosion to 100 times the brightness of a normal supernova.

“This discovery raises many more questions than it answers,” Krems said. “More work is needed to find out which of the several possible explanations is correct.”

Because astronomical transients can appear anywhere at any time, and are relatively transient in astronomical terms, researchers rely on large-scale surveys that can continuously monitor large areas of the sky to detect them and alert other observatories like Hubble to follow up. Notes.

Researchers say that a larger sample is needed to better understand this phenomenon. Coming telescopes to survey the entire sky, such as the Vera C. Rubin Earth Observatory, may be able to detect even more, depending on basic astrophysics.

Reference: “AT2023fhn (The Sparrow): A fast, bright blue optical transient at a large offset from its host galaxy” by AA Chrimes, PG Jonker, AJ Levan, DL Coppejans, N. Gaspari, BP Gompertz, PJ Groot, DB Malesani, A. Mummery, E.R. Stanway and K. Wiersema, accepted, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

arXiv:2307.01771v2

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, operates the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts science operations on Hubble and Webb. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, in Washington, DC

The international team of astronomers in this study consists of AA Chrimes (Radboud University, Netherlands), PG Jonker (Radboud University and Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Netherlands), AJ Levan (Radboud University, Netherlands); University of WarwickUnited Kingdom), D. L. Coppejans (University of Warwick, United Kingdom), N. Gaspari (Radboud University, Netherlands), B. P. Gompertz (University of Birmingham, United Kingdom), P. J. Groot (Radboud University, Netherlands; University of Cape Town and South African Astronomical Observatory, South Africa), D. B. Malesani (Radboud University, Netherlands; Cosmic Dawn Center (DAWN) and University of Copenhagen, Denmark), A. Mummery (Oxford Astrophysics, UK), R. Stanway (University of Warwick, UK) and K. Wiersema (University of Hertfordshire, UK).

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again