The clay bricks used to build one of history’s most epic civilizations now give scientists a new tool for understanding the history of our planet.

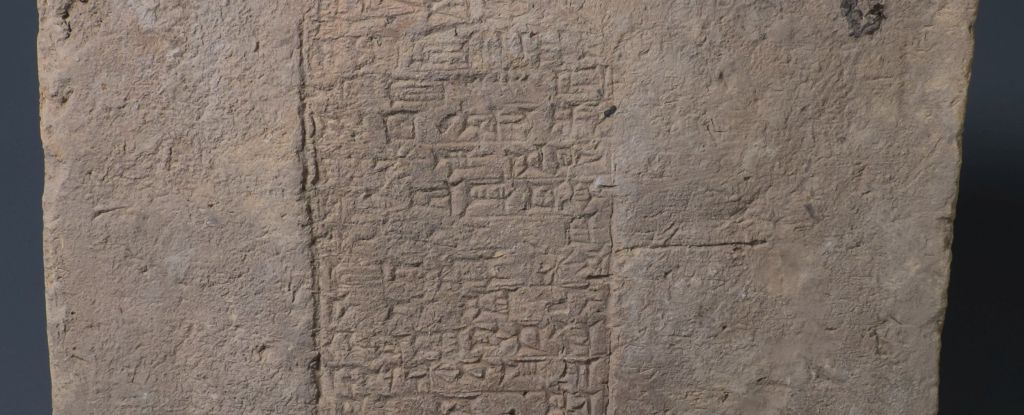

Mesopotamian bricks, made about 3,000 years ago, contain grains of iron oxide, which, in the correct interpretation, reveal amazing changes in the magnetic field that passes through the Earth and envelops it in a protective barrier.

This breakthrough comes in the form of a conveniently stamped description that allows scientists to determine the age of the bricks, which in turn allows for accurate dating of any geological records they contain.

This method gives us a new way to better understand how our planet’s magnetic field changes and evolves over time, which in turn can help us make better predictions about its current and future behavior.

“We often rely on dating methods such as radiocarbon dating to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia.” Archaeologist Mark Tawil explains From University College London.

“However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, usually cannot be easily dated because they do not contain organic materials. This work now helps establish an important dating baseline that allows others to take advantage of absolute dating using archaeological magnetism.”

The Earth’s magnetic field is not constant, but changes over time. They are created by the geodynamo at the heart of the planet. There, a rotating, loaded, electrically conductive fluid converts kinetic energy into electric and magnetic fields that rotate in the space around us. Changes in the magnetic field can be the result of external influences, Like the solar wind; Or from changes within the planet, Where the geodynamo moves.

Regardless of how they are caused, these changes can be recorded in the materials on the surface. For example, in molten magma, the magnetic grains will line up with the Earth’s magnetic field, and settle into that position as the magma cools and solidifies into volcanic rock. Scientists can use these rocks as a record of the magnetic field, an area of study known as… Ancient magnetism.

Led by archaeologist Matthew Howland of Wichita State University in the United States, a team of researchers studied bricks in Mesopotamia as a way to advance the study of Archaeological magnetism: The study of the Earth’s magnetic field as preserved in man-made objects.

This technique is very simple. Each of the 32 Mesopotamian clay bricks in the study was stamped with the name of the king who ruled at the time the bricks were made. In order to date the material, researchers narrowed down the likely range of years during which each king was likely to rule.

Next, they carefully cut a small piece from each brick, and used a magnetometer to measure the alignment of the microscopic grains of iron oxide contained within them. This technique allowed them to reconstruct the behavior of the planet’s magnetic field on a large scale over a period of about 2,000 years, from the third millennium to the first millennium BC.

They then compared their results with other reconstructions of the magnetic field derived from archaeological magnetic studies.

Collectively, this large body of data from around the world points to what is known as the Levantine Iron Age Geomagnetic Anomaly (LIAA), a mysterious spike in magnetic field strength believed to have occurred in what is now Iraq between about 1050 and 550 BC.

The team’s reconstruction also confirmed the existence of LIAA, providing one of the few records of the anomaly from within Iraq itself. Furthermore, the analysis revealed short, dramatic fluctuations during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II between about 604 and 562 BC, showing that the Earth’s magnetic field can change dramatically over short timescales.

The work is a double-edged feat: matching the bricks to the magnetic field works in the other direction, giving scientists a tool to confirm the dates when certain kings ruled Mesopotamia.

This is truly remarkable, because although we know the order of succession, the dates on which each king ascended the throne have remained uncertain, due to incomplete historical records.

“The geomagnetic field is one of the most mysterious phenomena in earth sciences.” says geophysicist Lisa Tookes Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the United States.

“The well-dated archaeological remains of the rich cultures of Mesopotamia, especially bricks inscribed with the names of specific kings, provide an unprecedented opportunity to study changes in field strength with high resolution, tracing changes that occurred over several decades or even less.”

The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again