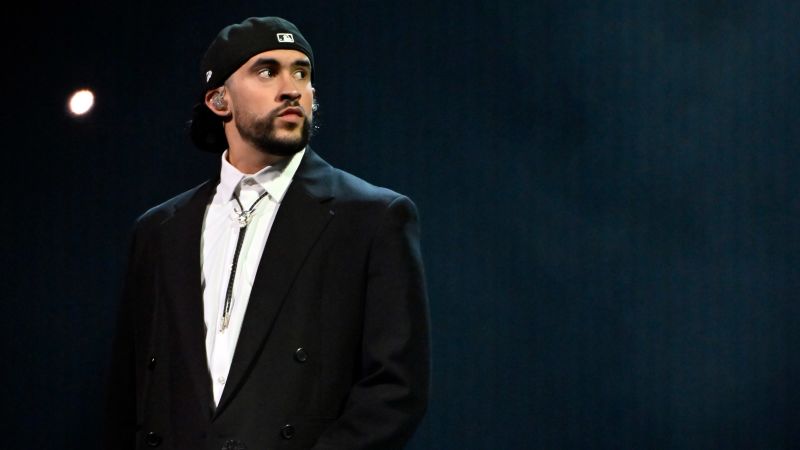

Study participant Freddy sits next to a bowl containing a sample of the scent, then approaches the bowl to check for a reward.

University of Bristol

Hide caption

toggle caption

University of Bristol

New research from the UK suggests that the smell of human stress affects dogs’ emotions as well as their decisions, leading them to make more pessimistic choices.

The study, published Monday in Scientific Reports JournalThis project was the result of a partnership between the University of Bristol, Cardiff University and the UK charity Medical Dogs.

This involved placing humans in a heated seat and then placing sweat-soaked rags and food bowls in front of more than a dozen dogs to see how they reacted to the stressful smell.

“Some people have looked at dogs’ ability to detect differences in scent, and they have done that,” says Dr Zoe Barr-Curtis, a veterinarian and PhD student at Bristol Veterinary School, who was the study’s lead author. “But no one has really looked at how that affects a dog’s emotions.”

Dogs are known to be trained to detect changes in levels of cortisol, a hormone that floods the body during times of stress, as service dogs do for people with certain health conditions.

But the researchers wondered how sniffing stress-related changes in the hormone cortisol might affect dogs’ emotional state.

“Being a species that has lived and evolved with us for thousands of years, it makes sense that dogs would learn to read our emotions because it could be useful for them to know if there is something threatening in the environment or some stressful factor that they need to be aware of,” Barr-Curtis explained.

How Researchers and Dogs Use Smell to Get Clues

To find out, the researchers first subjected human volunteers — who, importantly, were unknown to the participating pups — to a stress test.

They were forced to prepare a five-minute speech and deliver it on the spot—and worse—do a high-stress math task, in which the researchers “maintained serious expressions throughout to increase social anxiety.” They were then rewarded by sitting in a beanbag chair and watching a 20-minute video of forest and seascape scenes.

The researchers measured multiple markers of stress, including cortisol levels, heart rate and self-reported anxiety, during both sets of activities. They also collected samples of the participants’ breath and sweat by taping pieces of cloth under their armpits.

Meanwhile, 18 dogs of different breeds underwent their own experiments, being carefully trained to recognize the location and contents of several bowls in the study room.

Bar-Curtis says this setup is based on the famous test in which a person is shown a partially full glass and asked to distinguish whether it is half full or half empty.

“Their response may change depending on their mood at that moment, or perhaps their outlook on life at that time,” she explains.

Initially, the dogs were trained to learn that the food bowl on one side of the room always contained a food reward, while the bowl on the other side was always empty. Over time, the dogs became quick to approach the full bowl and slow to approach the empty bowl.

The researchers then changed the scenario, removing the two pots and placing a third pot between the two sites, resulting in what is called the ambiguous scenario.

“Do they approach quickly, optimistic that they will find a food reward in the bowl, or do they approach more slowly, with a more pessimistic view that there may not be food in the bowl?” Barr-Curtis says of the dogs.

That’s where the sweaty clothes come in. Dog owners, acting as handlers, would open a jar of rags and have the dog sniff it, before placing a bowl in front of them. The researchers ran the test multiple times, with stress and relaxation scents, in different arrangements, and with bowls in the three locations.

The researchers found that dogs were more reluctant to approach the bowl in the mystery location after smelling the scent of a stressed stranger — meaning they were more pessimistic about the presence of any food in it. In contrast, the relaxing scent had no measurable effect.

“This basically shows that the smell of stress may affect how [dogs] “People who have difficulty coping with ambiguous situations respond better to uncertainty,” explains Barr-Cortes. “They may be less likely to try something risky if they think they’ll be disappointed.”

Molly Byrne, a doctoral student at Boston College who studies comparative cognition and was not involved in the study, was impressed by the results but cautioned that there is still a lot we don’t know about how dogs perceive things, and all sorts of factors, including their life experiences, can influence the decisions they make.

For her, the study confirms that dogs may be less likely to believe their owner is in a bad mood, which makes sense.

“When your owner is training you, he probably won’t give you a lot of treats if he’s really stressed out,” says Byrne.

What do the results mean for dog lovers?

We already know that positive, reward-based training is good for the owner-dog relationship, says Barr-Curtis. But this study suggests that the opposite is also true: Dealing with the process under stress can have a negative impact on how a dog feels and learns.

“The important thing is that this highlights how well dogs can recognize moods,” she adds. “So keeping your relationship with your dog…based on positive reinforcement and happy, fun engagement is the best way to have a good relationship and a happy dog.”

Frustration during training can be a source of stress, Byrne points out, adding that “often the problem is just that the person is upset.”

The fact that the study relied on volunteers who were unknown to the dogs—which Barr-Curtis says shows that dogs’ response is universal and not learned—holds lessons even for people who don’t actively train or raise dogs.

It’s good to keep in mind that situations that are stressful for humans can also be stressful for dogs, says Byrne. For example, if you feel anxious in a crowd, your dog will likely feel anxious, too.

“If you’re stressed, you’re more likely to be tense and less patient,” she adds.[And it] This could literally change their behavior. I think that’s really, really important to know.

All dogs have the potential to be affected by stress, even if not all of them show it, says Barr-Curtis. She points to her own dog, a quiet retired racing dog named Darwin.

“I fully realize that even though he seems calm and composed, there are probably things going on in his mind that are still affected by my stress and other things going on,” she says.

Barr-Curtis adds that humans, who rely primarily on sight to understand their environments, may forget that dogs’ most dominant sense is smell, which gives them a completely different perspective on the world around them.

While this may be easier said than done, she says it’s just one of many reasons to de-stress — around dogs and in general.

“Travel specialist. Typical social media scholar. Friend of animals everywhere. Freelance zombie ninja. Twitter buff.”

More Stories

Taiwan is preparing to face strong Typhoon Kung-ri

Israel orders residents of Baalbek, eastern Lebanon, to evacuate

Zelensky: North Korean forces are pushing the war with Russia “beyond the borders”