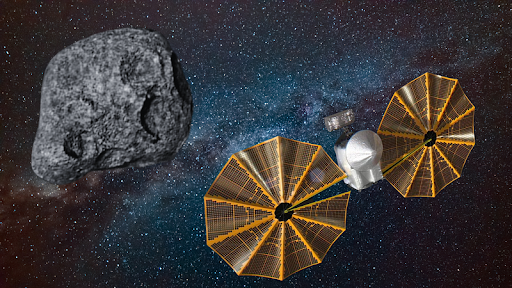

NASA’s Lucy spacecraft is about to make its first flyby of an asteroid on Wednesday, November 1.

When Lucy flies by the half-mile-wide asteroid, called Dinkenish, that moment will mark the beginning of the probe’s 12-lire, 10-person tour of the asteroids. Ultimately, this spacecraft’s planned legacy is to become the first to investigate Trojan asteroids — asteroids that follow Jupiter’s orbit around the Sun and are believed to be remnants of the formation of our solar system.

Lucy had been preparing for her visit to Dinkenish since September 3, keeping the small asteroid in sight as best she could. But on November 1, the spacecraft will get its first up-close look at the space rock.

“This is the first time Lucy has gotten a close look at an object that, up to this point, has been just an unresolved smudge in the best telescopes,” said Lucy principal investigator and Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) researcher Hal Levison. He said in a statement. “Dinkenish is about to be revealed to humanity for the first time.”

Lucy lifted off at 5:34 a.m. EDT (0934 GMT) on October 16, 2021, from Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard an Atlas V rocket. The spacecraft then returned to Earth for gravitational assistance one year later, on October 16, 2022. After passing 220 miles (350 kilometers) above Earth’s surface, Lucy shot toward the main asteroid belt about 300 million miles (480 million) away. kilometers) – which brings us to now.

Lucy’s Past: What’s in a Name?

Planning for the Lucy mission began when the project – part of the Discovery Program’s 2014 Announcement of Opportunities (AO) – was selected by NASA in 2017 from among 28 proposals that should have been ready for launch in 2021. Lucy originally got its name from a song The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds”, but the title also has a scientific inspiration. Lucy’s Mission shares its name with a famous fossil of one of the oldest known human ancestors that is part of the Australopithecus afarensis family. Interestingly, “Dinkinesh,” an Ethiopian word that translates from Amharic to mean “You are wonderful,” is actually another name for the same fossil.

Just as the fossil Lucy revealed important details about the origins of our species, the Lucy spacecraft promises to reveal more about the origins of our cosmic neighborhood. The latter will do this by investigating asteroids (Trojan asteroids) that are believed to be primitive “fossils” of our solar system, made up of material left over from the creation of the planets. This means that these asteroids are likely at least 4.6 billion years old, as that is when our solar system formed. This also means that the composition of the Trojan asteroids could show us which elements were present when Earth was still clumping together.

The Dinkinesh asteroid was only given its Lucy-related name in February 2023. Its previous designation was the less clever one “1999 VD57”. The new Dinkenish name officially arrived in January this year, following the decision to add Dinkenish to Lucy’s itinerary. Since then, Lucy’s operators have also nicknamed the space rock “Dinky.”

Lucy’s Gift: Hello “Dinky”

On November 1, Lucy will reach Dinkenish, and at 12:54 EDT (1654 GMT), it will make its closest approach to the asteroid, coming within 270 miles (430 kilometers) of the surface of the space rock.

This will be more than just a social visit, as Lucy’s flyby by Dinkenish is expected to represent an important test of the spacecraft’s instruments before it reaches its Trojan destination. For example, an hour before her close approach to Dinkenish, Lucy will begin tracking the target using her terminal tracking system.

Then, about 8 minutes before close approach, the spacecraft will begin collecting data about Dinkinesh using its color imager and infrared spectrometer. Once close enough to the asteroid, Lucy will begin collecting data using the high-resolution camera (L’LORRI) and the thermal infrared camera (L’TES). This continuous imaging and tracking of Dinkinesh will continue for about another hour.

“We will know what the spacecraft should be doing at all times, but Lucy is so far away that radio signals take about 30 minutes to travel between the spacecraft and Earth, so we cannot control an asteroid encounter interactively.” Evertz, Lucy’s chief engineer at Lockheed Martin Aerospace, said in the statement. “Instead, we pre-program all the science observations. After the science observations and flyby are complete, Lucy will redirect its high-gain antenna toward Earth, and then it will take approximately 30 minutes for the first signal to reach Earth.”

After Lucy reorients itself and resumes communications with Earth, the spacecraft will then continue to periodically image Dinkenish with L’LORRI over the next four days as it bids farewell to the asteroid.

Lucy’s Future: Hunting the Trojans

After this important test of the Lucy instruments, the spacecraft will return to Earth for another gravitational assist in December 2024. This boost will return it to the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, resulting in Lucy’s second scheduled flyby of the asteroid. This flyby will be another major asteroid belt object, the 2.5-mile-wide (4 km) space rock dubbed 52246 Donald Johansson – named after American researcher Donald Johansson, who co-discovered the Lucy fossil. Johansson.

After that, Lucy will finally head toward two Trojan swarms anchored on Jupiter’s orbital path.

The first flyby target of Troy is scheduled for August 2027, and will be a 40-mile (64-kilometer) wide asteroid called 3548 Eurybates. 3548 Eurybates is also accompanied by a small, half-mile (1 km) long, rocky satellite called Queta – meaning this will be a “two-for-one” flying experience for Lucy.

Lucy’s next target will be the dark, reddish asteroid 15094 Polymel. It will fly by this space rock in September 2027. At 13 miles (21 kilometers) in diameter, 15094 Polymelli is the smallest of Lucy’s targets. In fact, Polimil is also accompanied by a partner. This partner has not yet been officially named, but scientists have nicknamed it “Xuan.” Hopefully, Lucy will also catch a glimpse of Xuan.

Next, Lucy’s next step will be a flyby of the 25-mile-wide (40-kilometer) Trojan asteroid 11351 Leucos, which is expected to make a pass in April 2028. Because this asteroid rotates so slowly, it gets hotter. During the day and colder at night. However, the slow speed is a good thing for astronomers, because it means we can learn more about the materials that asteroids are made of as they move slowly.

In November 2028, Lucy will pass by the 32-mile-wide (51-kilometer) 21900 Orus, another dark-red asteroid believed to be rich in organic matter and carbon.

Last but not least, the final encounter of Lucy’s primary mission will be another binary stand as the spacecraft flies by the duo pair of asteroids, 617 Patroclus and Menoetius. Lucy is headed toward a big finish because these Trojan asteroids are the largest space rocks on her itinerary at 70 miles (113 kilometers) and 65 miles (104 kilometers) across, respectively. Just visiting these asteroids would be a huge accomplishment in itself, because they orbit the Sun at a high inclination above the plane of the solar system and are therefore very difficult for spacecraft to reach.

The binary asteroids will pass through a zone that Lucy can reach in March 2033. But the journey officially begins on November 1, with little Dinky.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again