On any given night, a “new star,” or star, will appear in the night sky. While it won’t light up the sky, it is a special opportunity to see a rare event that is usually difficult to predict in advance.

The star in question is T Coronae Borealis (T Krppronounced “te-kur-bur”). It is located in the constellation Northern Crownprominent in the Northern Hemisphere but also visible in northern skies from Australia, Aotearoa and New Zealand over the next few months.

Most of the time, T CrB, which is 3,000 light-years away, is too dim to see. But once every 80 years or so, it explodes with a bang.

A brand new star appears suddenly, but not for long. After just a few nights, it quickly fades away, disappearing back into the darkness.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

explosion of life

During the peak of their lives, stars derive their energy from nuclear fusion reactions taking place deep within their cores. Most of the time, hydrogen is converted into helium, creating enough energy to keep the star stable and shining for billions of years.

But T CrB has long passed its peak and is now a stellar remnant known as white dwarfIts internal nuclear fires have been extinguished, allowing gravity to compress the dead star dramatically.

T CrB also has a companion star – a red giant that has bloated as it ages. The white dwarf is sucking in the red giant’s bloated gas, forming what is called an accretion disk around the dead star.

Matter continues to pile up on the already extremely compact star, forcing ever-increasing pressure and temperature. Conditions become so extreme that they mimic what would have existed inside the core of a star. Its surface ignites in a wild thermonuclear reaction.

When this happens, the energy released makes T CrB 1,500 times brighter than usual. Here on Earth, it briefly appears in the night sky. With this dramatic re-entry, the star has expelled the gas and the cycle can begin again.

How do we know when it’s time?

TCrB is the brightest of the rare class of New recurrent tumors Recurring astronomical phenomena are those that occur every hundred years – a time scale that allows astronomers to discover their recurring nature.

Only ten new recurring novae are currently known, although more new novae may be recurring – but on much longer timescales and not easily tracked.

The earliest known date for a T CrB eruption is 1217, based on observations recorded in Medieval monastic recordSurprisingly, astronomers are now able to accurately predict its explosions as long as the new star follows its usual pattern.

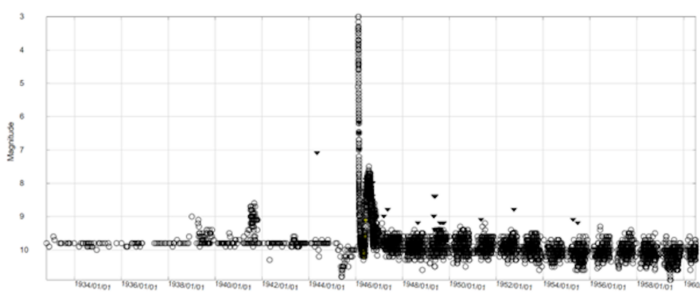

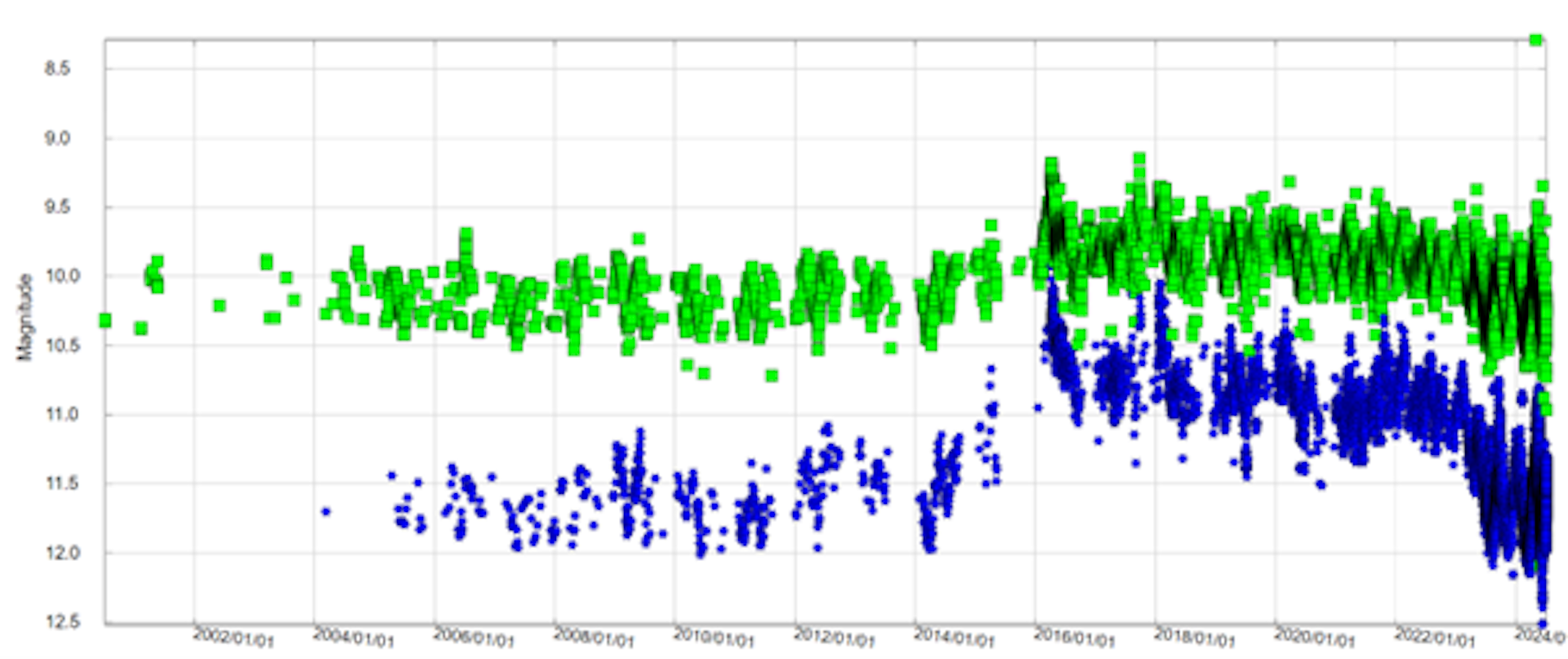

The star’s two most recent outbursts – in 1866 and 1946 – showed exactly the same features. About ten years before the outburst, T CrB’s brightness increased slightly (known as the high state) and then was followed by a brief dimming or decrease about a year after the explosion.

TCrB entered its high state in 2015 and the dip that preceded the eruption was observed in March 2023, putting astronomers on alert. The causes of these phenomena are just some of the current mysteries surrounding TCrB.

How can I see it?

Start stargazing now! It’s good to get used to seeing stars. Corona Borealis As it is now, so you get the full effect of the “new” star.

Corona Borealis is currently in its best observing position (known as Crossing the longitude) around 8:30pm to 9pm local time across Australia and Aotearoa. The farther north you are, the higher the constellation will be in the sky.

The new star is expected to be reasonably bright (magnitude 2.5): about as bright as Imai (Delta Crucis), the fourth brightest star in Southern CrossSo, it will be easy to see even from the city’s location, if you know where to look.

We won’t have much time.

We won’t have long to wait after it goes out. Its peak brightness will only last a few hours; in a week, T CrB will fade and you’ll need binoculars to see it.

It is almost certain that an amateur astronomer will alert the professional community to the moment T CrB explodes.

These dedicated and educated people routinely observe the stars from their homes in the hope of “what ifs,” thus filling an important gap in night sky observation.

American Variable Star Society (Doctors Without Borders) Its record contains more than 270,000 observations submitted for T CrB alone. Amateur astronomers here and around the world collaborate to monitor T CrB continuously for the first signs of an eruption.

Hopefully the new star will explode as expected sometime before October, because then the northern corona will leave the evening sky in the Southern Hemisphere.

Tanya HillSenior Curator (Astronomy), Museums Victoria and Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne, Museums Victoria Research Institute And Amanda CaracasAssociate Professor, Faculty of Physics and Astronomy, Monash University

This article was republished from Conversation Under a Creative Commons license. Read Original Article.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again