Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter. Explore the universe with news about amazing discoveries, scientific advances, and more..

CNN

—

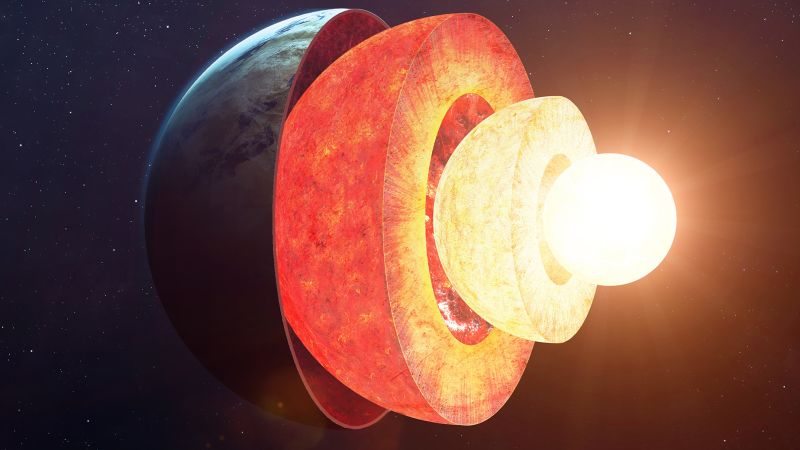

Deep within the Earth lies a solid metal sphere that rotates independently of our spinning planet, like a peak rotating within a larger peak, shrouded in mystery.

This inner core has intrigued researchers since it was discovered by Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann in 1936, and how it moves—how fast and in what direction—has been a subject of debate for decades. A growing body of evidence suggests that the core’s rotation has changed dramatically in recent years, but scientists remain divided on exactly what’s happening—and what it means.

Part of the problem is that it is impossible to directly observe or sample the Earth’s deep interior. Seismologists have gathered information about the motion of the inner core by examining the behavior of waves generated by large earthquakes that hit this region. The differences between waves of similar magnitude that pass through the core at different times have allowed scientists to measure changes in the inner core’s position and calculate its rotation.

“Differential rotation of the inner core was proposed as a phenomenon in the 1970s and 1980s, but seismic evidence was not published until the 1990s,” said Dr Lauren Waszczyk, a senior lecturer in physical sciences at James Cook University in Australia.

But researchers have debated how to interpret these results, “primarily because of the challenge of making detailed observations of the inner core, given its distance and the limited data available,” Waszek said. As a result, she added, “studies over the years and decades have differed on the rate of rotation, as well as its orientation with respect to the mantle.” Some analyses have even suggested that the core isn’t rotating at all.

Promising model Proposed in 2023 Scientists have described an inner core that once rotated faster than Earth itself, but now rotates more slowly. The core’s rotation matched Earth’s for a while, the scientists said. Then it slowed down even more, until the core began to move backward relative to the surrounding liquid layers.

At the time, some experts cautioned that more data was needed to support this conclusion, and now another team of scientists has provided compelling new evidence for this hypothesis about the rotation rate of the inner core. The research was published June 12 in the journal nature But this not only confirms the underlying economic slowdown, it supports the 2023 suggestion that this underlying slowdown is part of a long-term pattern of deceleration and acceleration.

forplayday/iStockphoto/Getty Images

Scientists study the Earth’s inner core to learn how the deep interior of the Earth formed and how activities are linked across all the surface layers of the planet.

The new findings also confirm that changes in rotation speed follow a 70-year cycle, according to one of the study’s authors. Dr. John VidalDean’s Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

“We’ve been arguing about this for 20 years, and I think this is the right answer,” Vidal said. “I think we’ve ended the discussion about whether the inner core is moving, and what its pattern has been over the past two decades.”

But not everyone is convinced it’s a done deal, and how the slowing inner core could affect our planet remains an open question — although some experts say Earth’s magnetic field could play a role.

The solid metal inner core lies 3,220 miles (5,180 kilometers) deep inside the Earth, surrounded by a liquid metal outer core. The inner core is mostly made of iron and nickel, and is estimated to be as hot as the surface of the Sun—about 9,800 degrees Fahrenheit (5,400 degrees Celsius).

Earth’s magnetic field pulls on this solid ball of hot metal, causing it to spin. At the same time, the gravity and flow of the liquid outer core and mantle pull on the core. Over many decades, these forces push and pull, causing variations in the core’s rotation rate, Vidal said.

The flow of metal-rich fluid in the outer core generates electrical currents that power Earth’s magnetic field, which protects our planet from deadly solar radiation. Although the direct influence of the inner core on the magnetic field is unknown, scientists have previously reported In 2023 The slowly rotating core may affect it and may also cause the length of the day to be slightly shorter.

When scientists try to “see” the entire planet, they generally track two types of seismic waves: pressure waves, or P waves, and shear waves, or S waves. P waves move through all types of materials; S waves move only through solids or highly viscous liquids, according to US Geological Survey.

In the 1880s, seismologists noticed that the S waves generated by earthquakes did not pass through the entire Earth, so they concluded that the Earth’s core was molten. But some P waves, after passing through the Earth’s core, appeared in unexpected places – the “shadow region,” as Lehmann put it. Call it – Created anomalies that were impossible to explain. Lyman was the first to suggest that turbulent P waves might interact with a solid inner core within the liquid outer core, based on data from a massive earthquake in New Zealand in 1929.

By tracking seismic waves from earthquakes that have passed through Earth’s inner core on similar paths since 1964, the authors of the 2023 study found that the rotation follows a 70-year cycle. By the 1970s, the inner core was spinning slightly faster than the planet. Then it slowed down around 2008, and from 2008 to 2023 it began moving in the opposite direction, relative to the mantle.

In the new study, Vidal and his colleagues observed seismic waves generated by earthquakes in the same locations at different times. They found 121 examples of such earthquakes that occurred between 1991 and 2023 in the South Sandwich Islands, an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Atlantic Ocean east of the southernmost tip of South America. The researchers also looked at shock waves that penetrated the core from Soviet nuclear tests conducted between 1971 and 1974.

The heart’s rotation affects the arrival time of the wave, Vidal said. Comparing the timing of the seismic signals as they hit the heart revealed changes in the heart’s rotation over time, confirming the 70-year rotation cycle. The researchers calculate that the heart is almost ready to start accelerating again.

Compared to other seismic studies that measure individual earthquakes as they pass through the core—regardless of when they occur—using only paired earthquakes reduces the amount of usable data, “making the method more challenging,” Waszczyk said. However, doing so also allowed the scientists to measure changes in the core’s spin more precisely, Vidal said. If his team’s model is correct, the core’s spin will start to accelerate again in about five to 10 years.

Seismometers also revealed that during the 70-year cycle, the core’s rotation slows down and speeds up at different rates, “which will need to be explained,” Vidal said. One possibility is that the metallic inner core isn’t as solid as expected. If it deforms as it spins, he said, that could affect the consistency of its rotational speed.

The team’s calculations also indicate that the nucleus has different spin rates for forward and backward motion, which adds “an interesting contribution to the discourse,” Waszczyk said.

But the depth and inaccessibility of the inner core means that doubts remain, she added. As for whether the core spin debate is truly over, Waszek said, “We need more data and improved multidisciplinary tools to investigate this further.”

Changes in the core’s rotation, while detectable and measurable, are almost imperceptible to people on Earth’s surface, Vidal said. When the core spins more slowly, the mantle speeds up. That shift makes the Earth spin faster, shortening the length of the day. But such rotational shifts translate into just a thousandth of a second in the length of a day, he said.

“In terms of how that impacts a person’s life?” he said. “I can’t imagine that means much.”

Scientists study the inner core to learn how Earth’s deep interior formed and how activities are linked across all layers of the planet beneath the surface. The mysterious region where the liquid outer core envelops the solid inner core is particularly interesting, Vidal added. As a place where liquid and solid meet, this boundary is “full of potential for activity,” like the core-mantle boundary and the mantle-crust boundary.

“We may have volcanoes at the inner-core boundary, for example, where solid and liquid materials meet and move,” he said.

Because the rotation of the inner core affects the motion in the outer core, it is thought that the rotation of the inner core helps power the Earth’s magnetic field, although more research is needed to uncover its exact role. Waszyk said there is much to learn about the overall structure of the inner core.

“New and future methodologies will be pivotal to answering ongoing questions about the Earth’s inner core, including rotation.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American, and How It Works.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again