Mars is shaken by earthquakes, but not all of them are caused by phenomena occurring beneath the surface – many of them occur in the wake of meteorite strikes.

Meteorites crash into the surface of Mars every day. After analyzing data from NASA’s InSight lander, an international team of researchers noticed that its seismometer, SEIS, had detected six nearby seismic events. These events were associated with the same atmospheric sound signature that meteoroids generate as they speed through the Martian atmosphere. Further investigation determined that these six events fall into a whole new class of seismic events known as very high-frequency events.

The impacts that generate marsquakes occur in fractions of a second, much less than the few seconds it takes for tectonic processes to cause quakes of similar magnitude. These are some of the key seismic data that have helped us understand how meteorite impact quakes occur on Mars. This is also the first time that seismic data has been used to determine how often impact craters form.

“Although a non-impact origin cannot be definitively ruled out for every VF event, we show that the VF class as a whole is plausibly caused by meteorite impacts,” the researchers said in a study published in the journal Nature Communications. Stady Recently published in Nature.

Seismic shift

Scientists have traditionally determined the rate of meteorite impacts on Mars by comparing the frequency of craters on its surface to the expected rate of impacts calculated using the number of lunar craters left by meteorites. Models of the lunar crater rate have then been modified to fit Mars conditions.

Looking at the Moon as a comparison wasn’t ideal, because Mars is more vulnerable to meteorites. And the Red Planet is not only a massive body with a stronger gravitational pull, but it’s also located near the asteroid belt.

Another problem is that lunar craters are often better preserved than Martian craters because there are No place in the solar system Craters in orbital images are often partially covered in dust, making them difficult to spot. Dust storms can complicate matters by covering craters with more dust and debris (something that can’t happen on the Moon due to the lack of wind).

The InSight spacecraft deployed its SEIS instrument after landing in Elysium Planitia In addition to detecting tectonic activity, the seismometer can determine the impact rate from seismic data. When meteoroids strike Mars, they produce seismic waves, just like tectonic earthquakes on Mars, and the waves can be detected by seismometers as they travel through the mantle and crust. A massive earthquake captured by SEIS was linked to a crater 150 meters (492 feet) across. SEIS would later detect five more Marsquakes, all of which were linked to an acoustic signal (detected by a different sensor on InSight) that is a telltale sign of a meteorite impact.

Significant impact

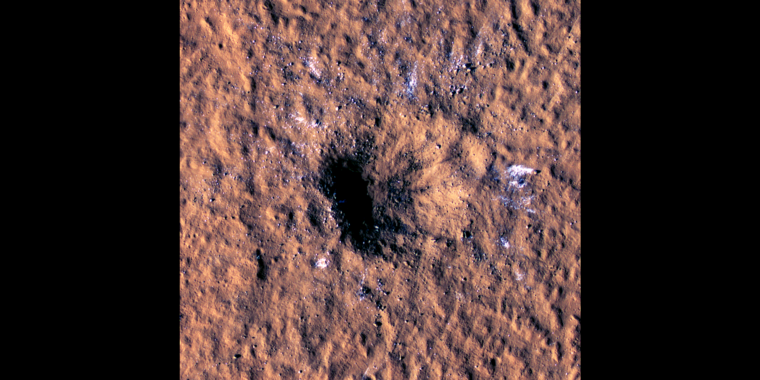

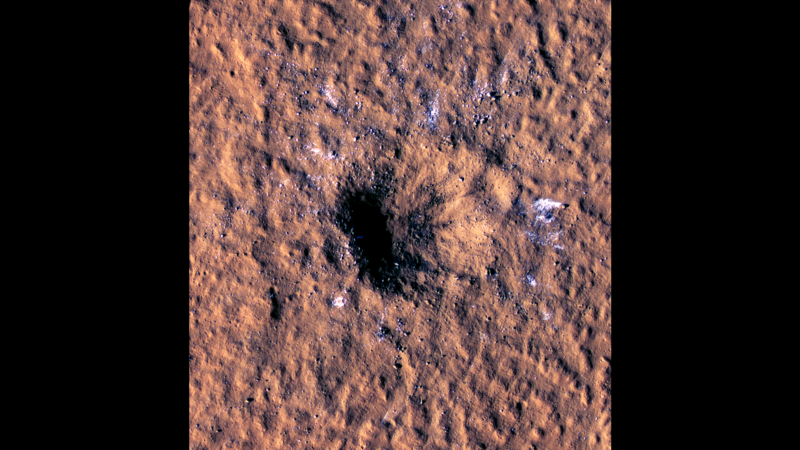

There was something else notable about the six impact-induced marsquakes detected using seismic data. Given the speed of the meteoroids (more than 3,000 meters or 9,842 feet per second), these events occurred faster than any other type of marsquake, even faster than quakes in the high-frequency (HF) category. That’s how they earned their own classification: very high-frequency, or VF, quakes. When the InSight team used the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s (MRO) Context Camera (CTX) to image the locations of the events captured by SEIS, new craters were visible in the images.

There are additional seismic events that have not yet been identified in connection with the craters. These are thought to be small craters formed by meteorites about the size of basketballs, which are very difficult to see in orbital images taken by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The researchers were able to use the SEIS data to estimate the diameters of the craters based on their distance from InSight (based on how long it took the seismic waves to reach the spacecraft) and the magnitude of the associated VF Martian quakes. They were also able to infer the frequency of the quakes captured by SEIS. Once they applied the frequency estimate based on the data to the entire surface of Mars, they estimated that about 280 to 360 VF quakes occur each year.

“The argument is strong that this unique class of earthquakes is consistent with impacts,” they said in the same study. Stady“Therefore, it is useful to consider the implications of attributing all visible sighting events to meteorite impacts.”

The discovery of these craters adds to estimates of the number of impact craters on Mars, many of which could not be seen from space before. What can VF impacts tell us? The rate of impact on a planet or moon is important for determining the age of that body’s surface. Using impacts has helped us determine that the surface of Venus is constantly being replenished by volcanic activity, while most of Mars’s surface has not been covered by lava for billions of years.

Determining how often meteorites strike Earth could also help protect spacecraft, and perhaps one day Martian astronauts, from potential hazards. The study suggests that there are periods when impacts are more or less frequent, so it might be possible to predict when the sky will be clear of falling space rocks—and when it won’t. Meteorites pose little danger to Earth because most of them burn up in the atmosphere. Mars has a much thinner atmosphere, allowing more meteorites to pass through, and there’s no parachute to protect it from meteor showers.

Physical Astronomy, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02301-z

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again