NASA agency Lunar ship Artemis 1 It returned to Earth on Sunday, cracking through the upper atmosphere at more than 24,000 miles per hour and enduring 5,000-degree reentry inferno before settling into a stellar Pacific Ocean to close out a 25-day, 1.4-million-mile test flight to the Moon and back.

Descending under three huge parachutes, the 9-ton Orion capsule gently smashed into the water 200 miles west of Baja California at 12:40 p.m. EDT, 20 minutes after encountering the first traces of the atmosphere observed at an altitude of 76 miles.

“I’m confused. This is an unusual day,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “It’s historic, because now we’re going back into deep space with a new generation.”

Network TV pool (top and bottom)

In a convenient if unplanned coincidence, the regression came 50 years to the day after the last Apollo 17 moon landing in 1972 and only 10 hours after SpaceX. Launched A Japanese lunar lander, sent for the first time in a purely commercial venture, from Cape Canaveral.

NASA commentator Rob Navias said at the moment Orion fell, referring to the Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites.

Nelson also spoke about Apollo, saying that President John F. Kennedy “stunned everyone of the Apollo generation, and said we were going to achieve what we thought was impossible.”

“It’s a new day,” said Nelson. “A new day has dawned. And the generation of Artemis is taking us there.”

NASA

A joint Navy-NASA recovery team was standing within sight of the Orion sprinkler to inspect the scorched capsule and, after one last round of testing, pulled it up to the flooded well deck of the USS Portland, an amphibious ship.

After pumping in seawater, Orion will rest on a protective cradle for the return trip to Naval Base San Diego and, eventually, a trip to Kennedy Space Center.

Re-entry and heating were the final major goals of the Artemis 1 test flight, giving engineers confidence that the 16.5-foot-wide Avcoat heat shield will function as designed when four astronauts return from the Moon after the next Artemis flight in 2018. 2024.

Mission manager Mike Saravin said Friday that heat shield testing was, in fact, a top priority for the Artemis 1 mission, “and it’s our first and foremost goal for a reason.”

“There is no arc jet or air thermal facility here on Earth capable of repeat entry at supersonic speed with a heat shield of this size,” he said. “It’s a completely new design for a heat shield, and it’s a piece of equipment that’s paramount to safety. It’s designed to protect the spacecraft and (future astronauts) … so the heat shield has to work.”

And it appears to have done just that, with no visible signs of any major damage. Likewise, all three main parachutes deployed normally as did the airbags needed to stabilize the capsule in cases of light perimeter inflation.

NASA

A successful test flight is “what we need to prove this vehicle so we can fly with a crew,” said Deputy Administrator Bob Cabana, a former space shuttle commander. “So here’s the next step, and I can’t wait…a few minor glitches along the way, but (overall) it performed flawlessly.”

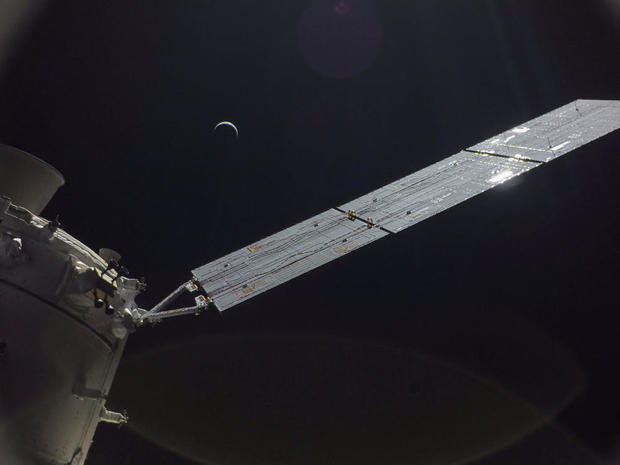

Launched November 16th In the first flight of NASA’s massive new Space Launch System rocket, an uncrewed Orion capsule was propelled from Earth’s orbit to the Moon to perform an exhaustive series of tests, putting the propulsion, navigation, power and computer systems through their paces in a deep space environment.

Orion flew through half of a “far retrograde orbit” around the Moon that carried it farther from Earth — 268,563 miles — than any previous human-classified spacecraft. Two critical launches of its main engine set up a low-altitude flyby of the lunar surface last Monday, which, in turn, sets the rover on course for a landing on Sunday.

NASA originally planned to bring the ship west of San Diego, but anticipation of a cold front bringing higher winds and rougher seas prompted mission managers to move the landing site south about 350 miles, to a point south of Guadalupe Island about 200 miles west. Baja California.

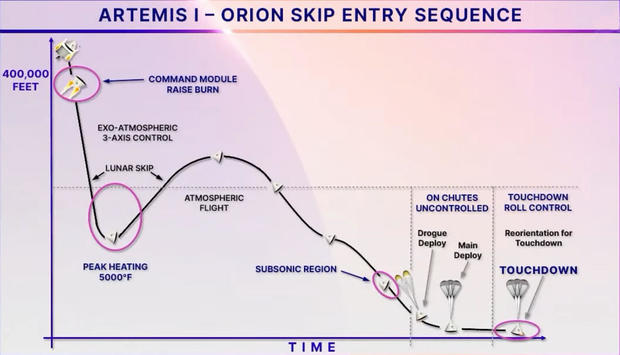

After a final course-correction maneuver early Sunday, the Orion spacecraft returned to the distinct atmosphere at 400,000 feet at 12:20 p.m.

The re-entry coil is designed to ensure Orion skips once through the top of the atmosphere like a flat stone skipping through calm waters before its final descent. As expected, Orion dropped from 400,000 feet to an altitude of about 200,000 feet in just two minutes, then climbed back up to about 295,000 feet before resuming its computer-guided fall to Earth.

Within a minute and a half of entry, atmospheric friction began generating temperatures through the heat shield of nearly 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit—half the temperature of the Sun’s visible surface—enveloping the spacecraft in an electrically charged plasma that blocked communications with flight control instruments for five years. approx years. Minutes.

NASA

After a two-and-a-half-minute communications failure during its second descent into the lower atmosphere, the spacecraft continued to slow as it closed into the landing site, slowing to about 650 mph, roughly the speed of sound, about 15 minutes after entry began.

Finally, at an altitude of about 22,000 feet and at a speed of just under 300 miles per hour, small cyclist parachutes deployed, and the protective cover pulled along with three pilot lanes. Finally, in a welcome sight for the nearby recovery crew, the capsule’s main parachutes took off at about 5,000 feet, slowing Orion to 18 mph or so for a splash.

The duration of the expedition was 25 days, 10 hours and 52 minutes.

“It was an amazing mission. We accomplished all of our major mission goals,” said Michele Zaner, Orion mission planning engineer. “The car has performed as well as we had hoped and in many ways even better.

“This is the furthest any human-classified spacecraft has ever traveled, and it required a lot of complex analysis and mission planning. To see it all come together and to have such a successful test mission was amazing.”

While the flight controllers experienced still-unexplained glitches in their power system, the initial “burlesque” with star tracking and degraded performance from the phased array antenna, the ESA-built Orion spacecraft and service module generally worked well, achieving Almost everything. of their main goals.

NASA (both)

If all goes well, NASA plans to follow up on the Artemis 1 mission by sending four astronauts around the moon on the program’s second flight — Artemis 2 — in 2024. The first moon landing will follow in the 2025-26 timeframe when NASA says the first will set foot. Introduce the next woman and man on the Moon near the South Pole.

While the 2024 flight seems achievable based on the results of the Artemis 1 mission, the Artemis 3 lunar landing faces a more difficult schedule, requiring a good performance during the Artemis 3 mission and the successful development and testing of a lunar lander that NASA pays SpaceX $2.9. billion to develop.

The probe, which is a variant of the company’s Starship rocket, has not yet flown into space. But it will require several robotic refueling trips in low Earth orbit before heading to the moon to await a rendezvous with the astronauts launched aboard the Orion capsule.

SpaceX and NASA have provided some details about the development of the Starship lunar lander, and it is not yet known when it will be ready to safely transport astronauts to the moon.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again