Now I know how a footballer feels when he scores at Wembley, and what it feels like when he appears on the Glastonbury Pyramid stage. To my absolute sincerity, in the auction room a little over a week ago, I fulfilled my lifelong ambition for more than half a century.

I couldn’t stop beating the air for joy and dancing around the room to the amazement of the onlookers.

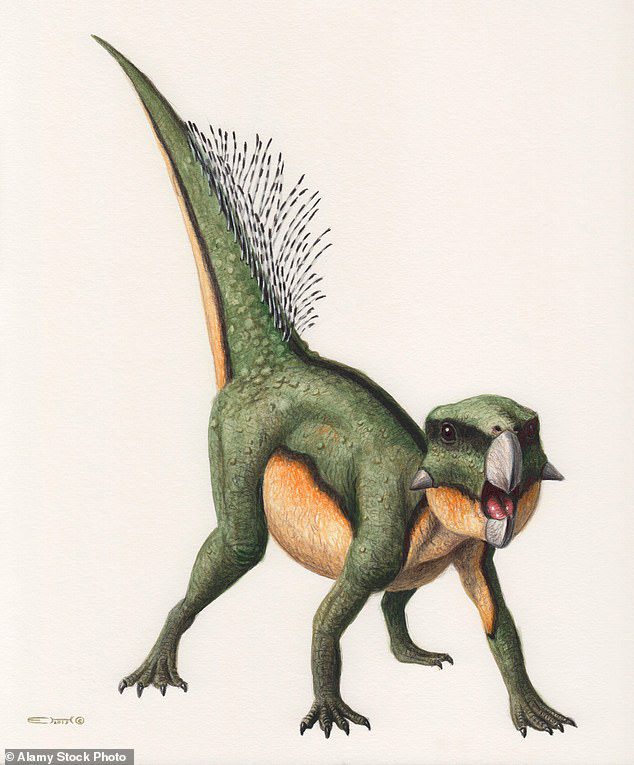

Because I bought a dinosaur. The fossilized skeleton of Psittacosaurus, a 120-million-year-old lizard parrot, is no less.

It was quite simply one of the greatest moments of my life, an unbeatable feeling. Days later, I’m still on cloud nine.

My happiness was magnified by the fact that my successful bid was far less than I was willing to pay. The catalog estimate was from £4,000 to £6,000, and I knew if it went over that limit, I was spoiled.

My wife knew how badly I desired to possess this extraordinary effect, but she would not allow me to rearrange the house. And I was pretty sure that a string of bids from billionaire fossil collectors would push the price over £10,000 in seconds.

In fact, I was certain that a whole specimen of Psittacosaurus was worth at least twice that.

Author and historian Tom Holland celebrates as if he won Wimbledon after fulfilling his childhood dream of owning a dinosaur, in fossil photo

Instead, the auctioneer started the auction with £3,500 – and I was the only bidder. Can you blame me for raising my fist like a Grand Slam tennis star and then jumping up to dance gleefully?

The auctioneer later said I was the happiest customer he had ever seen. And yes, you probably are.

The entire scene was captured on CCTV at the auction house, Woolley & Wallis of Salisbury. As I jump around, my father Martin can be seen sitting next to me with his arms softly folded. It’s fair to say he’s always been less personified than me.

Now the skeleton has joined my family in our house. Since it’s a parrot lizard, so named because of its curved beak that evolved to help it tear apart plants that were its primary food, my daughters and I christened it Polly.

By the time the auction started, my father and I had searched Polly in the auction house’s showroom. I knew it was in perfect condition, its bones wedged in a glass-covered display case on a bed of sand, as if a paleontologist had just scraped a covering from the ground.

The exhibition was owned by private collectors, who bought it at a museum in Hungary, and before that it was on display in a museum in New Zealand.

I first heard of its existence from my brother James, also a historian, who discovered it while browsing the Georgian furniture that makes up the bulk of the Woolley & Wallis catalog.

James knew how much I longed for a real, complete dinosaur skeleton. As a boy, my favorite birthday was going to the Natural History Museum in London, marveling at Diplodocus in the main hall and plesiosaur fossils in display cases.

On school holidays, I loved nothing more than looking up the coast around Lyme Regis in Dorset or on the Isle of Wight, hoping to discover an amazing fossil.

My historical hero was Mary Anning, who first discovered an ichthyosaur skeleton in 1811 when she was 12, helping to dismantle the prevailing scientific theory that the Earth was barely 6000 years old.

I have found ammonites, which are round, shell-like fossils very prevalent on the southern coast, but have not been able to extract any ichthyosaurs. My long-suffering parents will tell you it wasn’t out of a desire to try.

When I was a kid in the ’70s, not much was known about dinosaurs, and most books on the topic were aimed at young children or graduate experts.

As I entered my teens, my obsession waned—or rather, it was transferred to a new subject, the Roman Empire. Like dinosaurs, the ancient Romans are flashy, fierce, and extinct. The Romans are tyrannosaurs of antiquity, the crest of predators, red in the teeth and claw.

My first book in history was a study of the end of the Roman Republic, the years before Julius Caesar’s assassination.

My fascination with that era is matched by the enthusiasm I had as a boy for dinosaurs. This childhood sense of wonder has been revived in recent years. We live in the period of new discoveries, the golden age of dinosaur lovers, where the fossilized remains of previously unknown species are identified almost weekly.

Computer animation allows digital artists to recreate these adorable animals with extraordinary precision and clarity. The Prehistoric Planet series on Apple TV+, narrated by Sir David Attenborough, is so realistic that it’s easy to imagine we’re watching real wildlife documentaries. The Internet gave me access to unlimited expert research. I follow many of the world’s brightest paleontologists on Twitter, they are the most generous of the groups, always willing to sacrifice their time to answer my eager questions.

Parrot’s face: what did a toms psittacosaurus dinosaur look like

Dinosaur hunting will always be a hobby for me, not a profession. I recorded a show for Radio 4, an edition of our special correspondent, in which I visited the extraordinary Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Alberta, Canada.

There, I saw dinosaur feathers preserved in amber (yes, many were feathered, just like the birds that are its descendants).

Three complete dinosaur skeletons were displayed, along with a rock that revealed the exact moment in geological time when an asteroid hit Earth, 66 million years ago, wiping out the non-avian dinosaurs.

I’ve also attended excavations, including one in the wilds of Wyoming, US, where I saw an enormous sauropod leg being excavated along a stretch of desert known as the Jurassic Mile. But I wouldn’t have the knowledge or the money to lead an archaeological expedition, unfortunately more.

My brother understood all this and urged me to try my luck at auction. When my father and I arrived, our hopes for success seemed slim — and diminished too much to take our seats. We were the only members of the audience.

Having watched the auctions on TV, I was expecting a crowded room of bidders waving papers and indicating their interest with winks and gestures.

Instead, on a row of tables behind empty chairs, employees at computer stations sat with phone speakers, taking bids online.

My heart sank. It might just mean that dinosaur fans in Silicon Valley were calling, ready to move tens of thousands of pounds at the push of a button.

There were over 50 pieces to sell before Psittacosaurus came along, and my confidence ebbed with each piece. There were a few other fossils on sale and I decided, in order to make sure the afternoon wasn’t completely washed out, to bid on one or two.

I had the pleasure of getting a Mosasaur’s jawbone, if only because this is the giant marine reptile that jumps out of a swimming pool in the 2015 movie Jurassic World and sticks to a flying petranodon. . . And an unlucky employee named Zara.

Another hundred pounds secured me a fossil called simply “Dinosaur Bones.” These were prizes but they weren’t what I came for.

One of the reasons I was so keen on buying Psittacosaurus was its flawless source. A troublesome trade has arisen in excavations, uprooted from the ground by unlicensed excavators who make no effort to preserve the site and cause massive damage to places of great scientific value.

The 54-year-old man (pictured Tom Holland) went with his father to the sale in Woolley & Wallis, of Salisbury, Wales, to make a presentation on the skeleton of a Psittacosarus (parrot lizard) 97.5 to 119 million years old

This is similar to the illegal sale of antiquities from historical sites. I despise these ruinous merchants, who are no better than thieves.

I had my sights set on an item that was owned by at least two museums, and so I was confident that it had been responsibly acquired.

After the agony of waiting, Lot 698 appeared. It was described as a “Psitosaurus skeleton, Lower Cretaceous period, 119 million to 97.5 million BC” – that is, before the present.

The description read: “Bird-like skull and mouth beak, set on a natural desert sand environment, in a polished 85cm hardwood case.”

The catalog added that it was “notable for its bird-like appearance. Despite their small stature and lack of horns, they were part of the Ceratopsia group that included dinosaurs such as Triceratops.

My daughters, who had never before shared my joy with dinosaurs, fell in love with Polly – although, of course, what really pleased them was the scene I watched on CCTV, unable to control my excitement.

There is now a family showdown over where Polly will be shown. Girls want it on the wall in the kitchen where everyone can admire it.

But I think she will have to go to my studies, where I can stare at her while I work. . . And where no one can see me as I do the dinosaur victory dance every day.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again