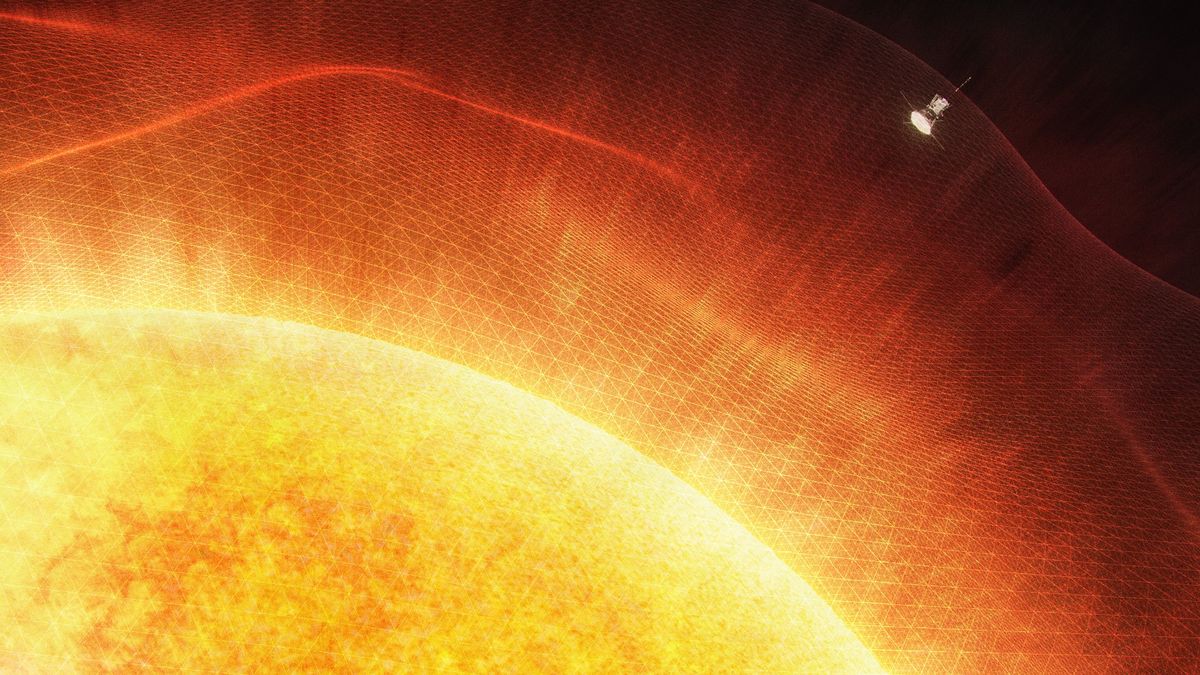

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has become the first spacecraft to fly past a planet Coronal mass ejection (CME) from the Sun, and captured the entire event on camera.

The stunning video shows the spacecraft passing through the massive solar flare on September 5, 2022. The probe flew through the wake of the frontal wave of the plasma wave (shock wave) before blasting out the other side.

By studying this daring work, scientists will piece together more of the Sun’s mysterious internal dynamics in an effort to better predict solar flares that threaten Earth. They published their findings exactly a year later on September 5 Astrophysical Journal.

Related: Rare streaks of light over the United States are a sign that solar maximum is rapidly approaching

“This is the closest to the Sun we have ever observed from the CME.” Nour Rawafia project scientist at the Parker Solar Probe at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, He said in a statement. “We have never seen an event of this magnitude at this distance.”

Coronal ejections are smoke ring-like explosions released from sunspots, areas on the Sun’s surface where they are strongest Magnetic fields, which arise from the flow of electrical charges, form nodes before suddenly cutting off. Once fired, a coronal ejection travels millions of miles per hour, sweeping up charged particles from the solar wind to form a giant, compact wavefront.

The Parker Solar Probe was launched toward the Sun in August 2018. Equipped with a heat shield and radiators to counter nearby solar energy, the probe was flying just 5.7 million miles (9.2 million km) above the Sun’s surface when its camera detected the CME. Rolling on its wing.

Not long afterward, the spacecraft fell upside down into the leading edge of the solar tidal wave, being struck by swirls of plasma as sparks from the solar wind filtered through its lens.

The solar probe spent two days observing the sun’s burps, enabling physicists to study the evolution of a coronal ejection in unprecedented detail. Scientists monitored three stages in the development of the eruption. The first two – shock wave and solar energy plasma, followed by the streaming solar wind – which has been observed before. But the third stage – the wake of slow-moving particles – puzzled them.

“You try simplified models to explain certain aspects of the event, but when you’re close to the sun, none of those models can explain everything,” said the study’s lead author. Orlando RomeoThe UC Berkeley space physicist said in the statement. “We’re still not entirely sure what’s going on there or how to connect it to the other two departments.”

Knowing how solar flares work is vital to protecting our planet from severe geomagnetic storms. Although the Earth’s magnetic field can absorb most of the glancing hits from a coronal ejection, more intense geomagnetic storms can distort it, sending satellites crashing to Earth, burning out electrical systems and possibly crippling the Internet.

The largest solar storm of modern times was the Carrington Event of 1859, which released approximately the energy equivalent of 10 billion 1-megaton atomic bombs. After colliding with Earth, the powerful stream of solar particles jammed telegraph systems around the world and caused aurora brighter than the light of a full moon as far south as the Caribbean.

Scientists warn that if a similar event occurred today, it would cause trillions of dollars in damage, lead to widespread power outages, and put thousands of lives at risk. A solar storm in 1989 released a billion-ton plume of gas and caused power outages across Quebec. NASA reported.

“Web maven. Infuriatingly humble beer geek. Bacon fanatic. Typical creator. Music expert.”

More Stories

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video and photos)

A new 3D map reveals strange, glowing filaments surrounding the supernova

Astronomers are waiting for the zombie star to rise again