His death was confirmed by the Pace Gallery and Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, which he represents. The cause was complications from the fall, said Adriana Elgarsta, Pace’s director of public relations.

No pop artist—not even his contemporaries Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein—created a body of public works to rival his. He said, “Art should mean more than just producing things for galleries and museums.” Los Angeles Times in 1995. “I wanted to put art into the experience of life.”

In 2017, reflecting on the career of Mr. Oldenburg, New York Times arts writer Randy Kennedy Note that It’s easy to “forget how radical his work was when it first appeared, broadening the definition of sculpture by making it more human and more cerebral at the same time.”

The external installations of Mr. Oldenburg included a Giant cherry balanced on a spoon in the Sculpture Garden at the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis; a Huge steel clothespins in Philadelphia Center Square; 20 tons Baseball Bat in front of the Chicago Social Security Administration building; and 38 feet long flashlight at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas.

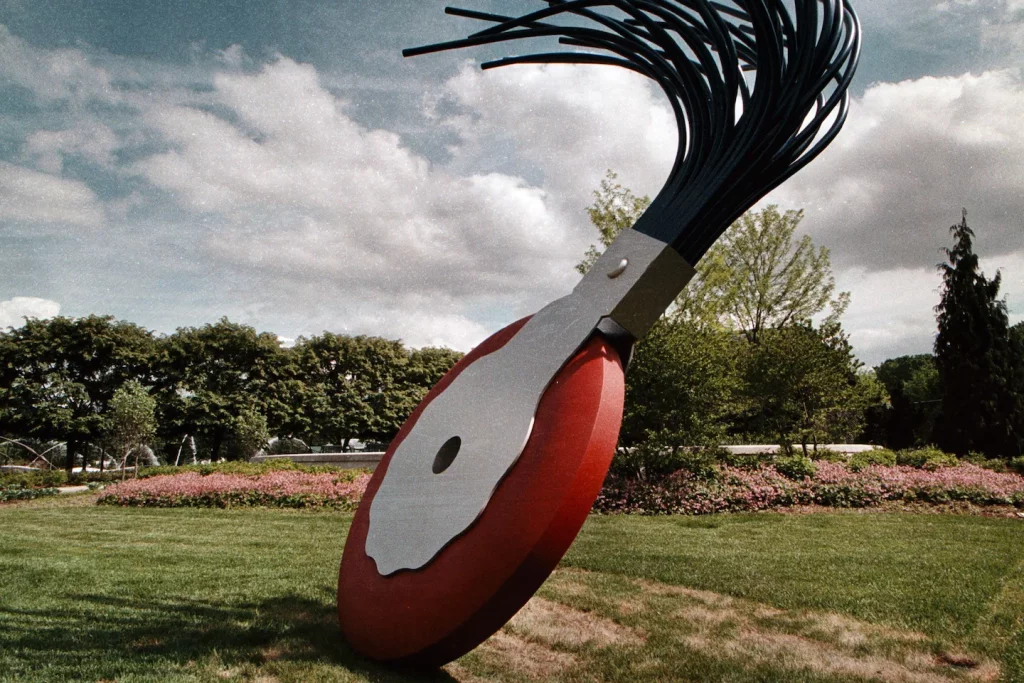

In Washington, his work is represented by a giant of steel and fiberglass typewriter eraser In the Sculpture Garden at the National Gallery of Art. Although the statue’s subject matter is a mystery to many younger visitors, its giant red wheel and wavy whiskers give it a compelling look.

At least one of Oldenburg’s devious proposal for the capital never materialized: a plan to replace the Washington Monument with giant scissors.

In the catalog of the 1973 exhibition “Claes Oldenburg: Object into Monument” at the Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. Oldenburg described the ideas behind the scissors. As the piece depicts, the red knobs would be buried in deep basins, their exposed blades open and closed within a day.

“Like scissors,” he wrote, “the United States is screwed together,” “two fierce parts destined in their arc to meet as one.”

Mr. Oldenburg may not have expected the scissors to be made. David Bagel, professor of art theory and history, wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2004 that Mr. Oldenburg’s “unreasonable proposals” were “more often than not great excuses for making wonderful drawings.” (In the case of scissors, one such drawing is in the collection of the National Gallery).

The second wife of Mr. Oldenburg, the Dutch-born sculptor, Cosge van Bruggen, was his collaborator from 1976 until her life. death in 2009. Although critics have sometimes questioned the extent of Van Bruggen’s role, the pair maintained that their role was a true artistic partnership. They said that the ideas of the statues were jointly developed. Then Mr. Oldenburg made drawings while she was dealing with manufacturing and positioning.

Mr. Oldenburg’s work delighted collectors as well as critics. His 1974 book “Ten Foot Clothespins” sold for more than $3.6 million at auction in 2015. In 2019, he sold his 450 notebook archive (plus thousands of drawings, photographs, and other documents) to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.

When Mr. Oldenburg arrived in New York in 1956, the era of Abstract Expressionist painting was drawing to a close. Young artists were pioneers in conceptual, performance, and installation art. After spending two years painting, Mr. Oldenburg threw himself into the new movements. “I wanted a job that says something, is messy, and is a bit vague,” he told The New York Times.

His first solo exhibition, in 1959 at Judson Memorial Chapel in Greenwich Village, consisted largely of abstract sculptures made of paper, wood, and string—things he said he had found on the street. Kennedy reported in the Times that his early work, “based on ostracism and hiatus, on the foundations and exuberance of modern life—was successful from the start with his contemporaries.”

In 1960, while working as a dishwasher in Provincetown, Massachusetts, Mr. Oldenburg found himself fascinated by the shapes of food and cutlery. In early 1961, he unveiled an installation called “The Shop” consisting of plaster models of actual groceries.

At that point, his colors became “very, very strong,” as Mr. Oldenburg said in a Recorded speech in 2012. And it became a graceful piece. “My act is really by touch,” he said. “I see things in the tour, and I want to make them in the tour. I want to be able to hit them and touch them.”

For a second copy of The Shop, at the end of 1961, Mr. Oldenburg rented a real storefront on Manhattan’s East Second Street. There’s a 10-foot ice cream cone display, a 5-by-7-foot hamburger and a nine-foot piece of cake. The pieces were made of cloth, and their chief seamstress was Patricia Moczynski, better known as Patti Mucha, an artist who was married to Mr. Oldenburg from 1960 to 1970. These were among the hundreds of soft sculptures he produced over the years.

According to New York Museum of Modern Artwho owns a label for “The Store”, the piece was a “milestone in pop art” that “heralded Oldenburg’s interest in the slippery line between art and merchandise and the artist’s role in self-promotion”.

By the mid-1960s, Mr. Oldenburg was an international art star. In 1969, he was the subject of the first major pop art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The show included more than 100 of his sculptures (including a re-creation of “The Shop”) and dozens of drawings.

But he was already thinking outside the confines of museums and galleries.

In 1969 he established “Lipstick (ascending) on caterpillar tracks,” Giant lipstick with an inflatable tip mounted on a plywood base resembling military tank bases. Commissioned by a group of Yale architecture students, it is parked in a prominent place on the university’s campus.

The sculpture was a physical embodiment of the anti-war slogan “Make love, not war” and a pulpit from which speeches could be given. But in 1974 (after Mr. Oldenburg had rebuilt the piece out of metal), the university moved it to a lesser-known location.

After the “lipstick”, Mr. Oldenburg created one “monumental monument” after another. Robinson Crusoe’s large umbrella is included in Des Moines. A Brobdingnagian Electrical Plug in Oberlin, Ohio; and colossal Cleveland rubber stamp. It was at times obvious how to relate the piece to the site only to Mr. Oldenburg and van Bruggen.

Oldenburg and van Bruggen sometimes collaborated with architect Frank Gehry, who combined them giant binoculars At the West Coast headquarters he designed for Los Angeles advertising agency Chiat/Day, which opened in 1991. (The periscope stands as a sort of driveway through which cars enter the building’s garage.)

Claes Thor Oldenburg was born in Stockholm on January 28, 1929. His mother was a concert singer, and his father was a Swedish consular official whose job required the family to move frequently.

Oldenburg moved to Chicago in 1936. Claes’ strongest memories of that period, he said, were of his mother filling notebooks with pictures from American magazines, including advertising photographs similar to those that appeared later in his work.

Mr. Oldenburg studied literature and art at Yale University. After graduating in 1950, he worked as a reporter in Chicago while taking art classes at night. He also spent some time in San Francisco, where he made a living drawing almond mites for pesticide ads, before moving to New York. For decades, he divided his time between Lower Manhattan and Beaumont-sur-Dimmy, France.

President Bill Clinton awarded him the National Medal of Arts in 2000.

Among the survivors are two sons-in-law, Martje Oldenburg and Paulus Kapten; and four grandchildren. His younger brother Richard, who died in 2018, spent 22 years as director of the Museum of Modern Art, later becoming president of Sotheby’s America.

Despite all of Mr. Oldenburg’s success, only a small part of his proposed monuments has been built.

Unrealized ideas include the planting of a giant rear-view mirror – a symbol of a backward culture – in London’s Trafalgar Square (1976) and the replacement of the Statue of Liberty with a giant electric fan to blow up immigrants at sea (1977).

He also suggested a drainpipe for Toronto, a windshield wiper for Grant Park in Chicago, an ironing board for Manhattan’s Lower East Side and bananas for Times Square, as well as scissors for Washington.

Sometimes, he wasn’t expecting to be taken seriously. in recorded interview The owner of the 2012 exhibition in Vienna, Mr. Oldenburg said, “The only thing that really saves the human experience is humour. I think without humor it wouldn’t be much fun.”

revision: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the survivors of Claes Oldenburg include three grandchildren, based on inaccurate information from the Paula Cooper Gallery. He is survived by four grandchildren. The article has been corrected.

“Freelance entrepreneur. Communicator. Gamer. Explorer. Pop culture practitioner.”

More Stories

Francis Ford Coppola talks about kissing in video while filming ‘Megalopolis’

John Mayall, influential blues musician, dies aged 90

Whitmer Promotes The Iron Sheik After Hulk Hogan’s GOP Convention Speech