Written by Rebecca Morrell and Alison Francis BBC News Science

Iceland woke up to another day of fires this week, as towering lava fountains lit up the dark morning sky.

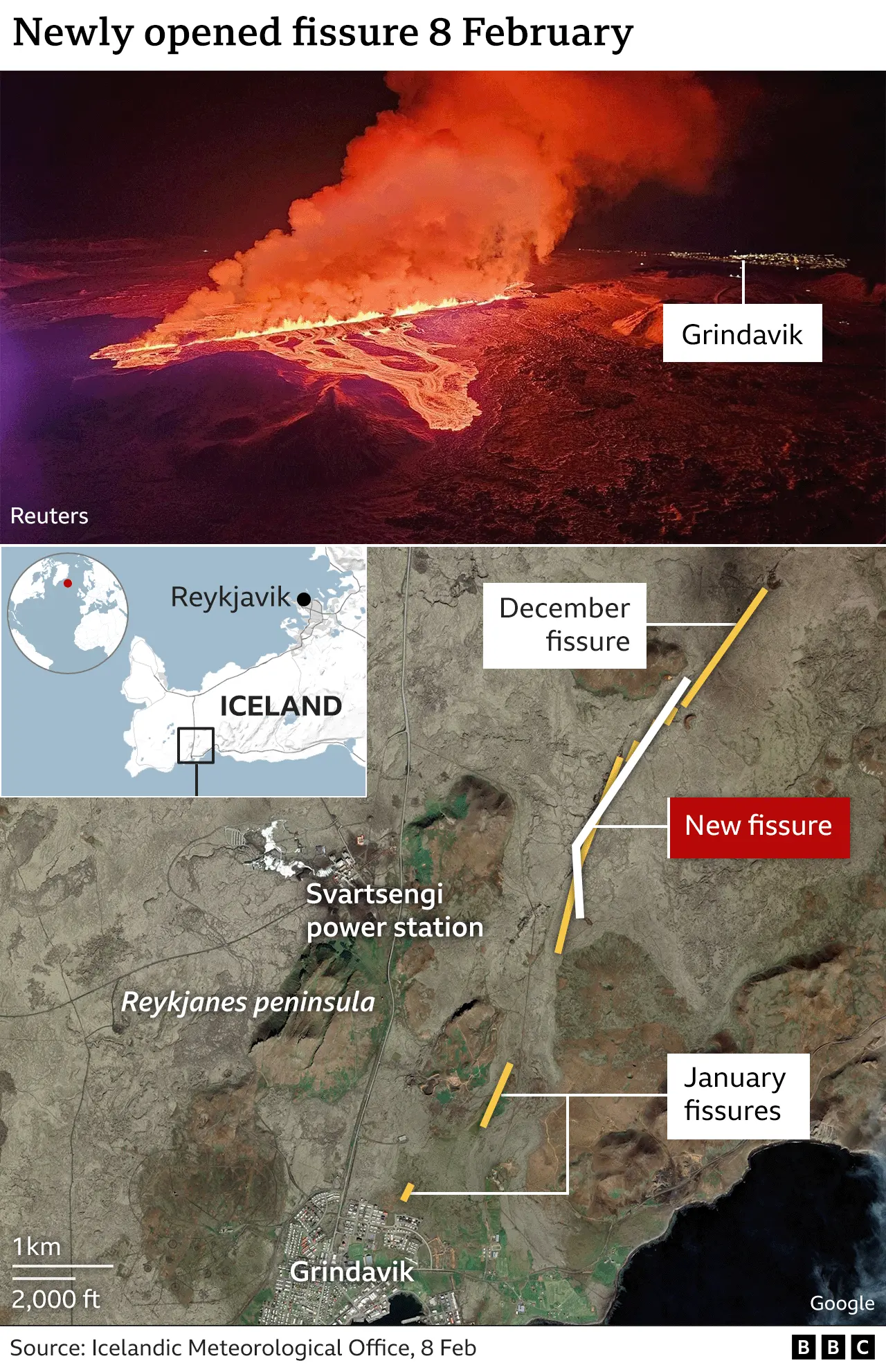

This time the evacuated town of Grindavik survived, but molten rock still wreaked havoc, swallowing a pipe that supplies heat and hot water to thousands living in the area and cutting off the road to the Blue Lagoon tourist area.

This is the third short-lived eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula since December 2023 and the sixth since 2021. But scientists believe this is just the beginning of a period of volcanic activity that could last decades or even centuries.

What is happening?

Reuters

ReutersIceland is no stranger to volcanoes, as it is one of the most volcanically active places in the world.

This is because the country sits above a geological hotspot, where plumes of hot material deep within the Earth rise toward the surface.

But Iceland also lies on the border between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates. These plates pull apart very slowly, creating space for hot molten rock – or magma – to flow upward.

As magma accumulates underground, pressure increases until it breaks the surface in an eruption (at which point the hot rocks are called lava).

There are over 100 volcanoes throughout Iceland and over 30 are currently active.

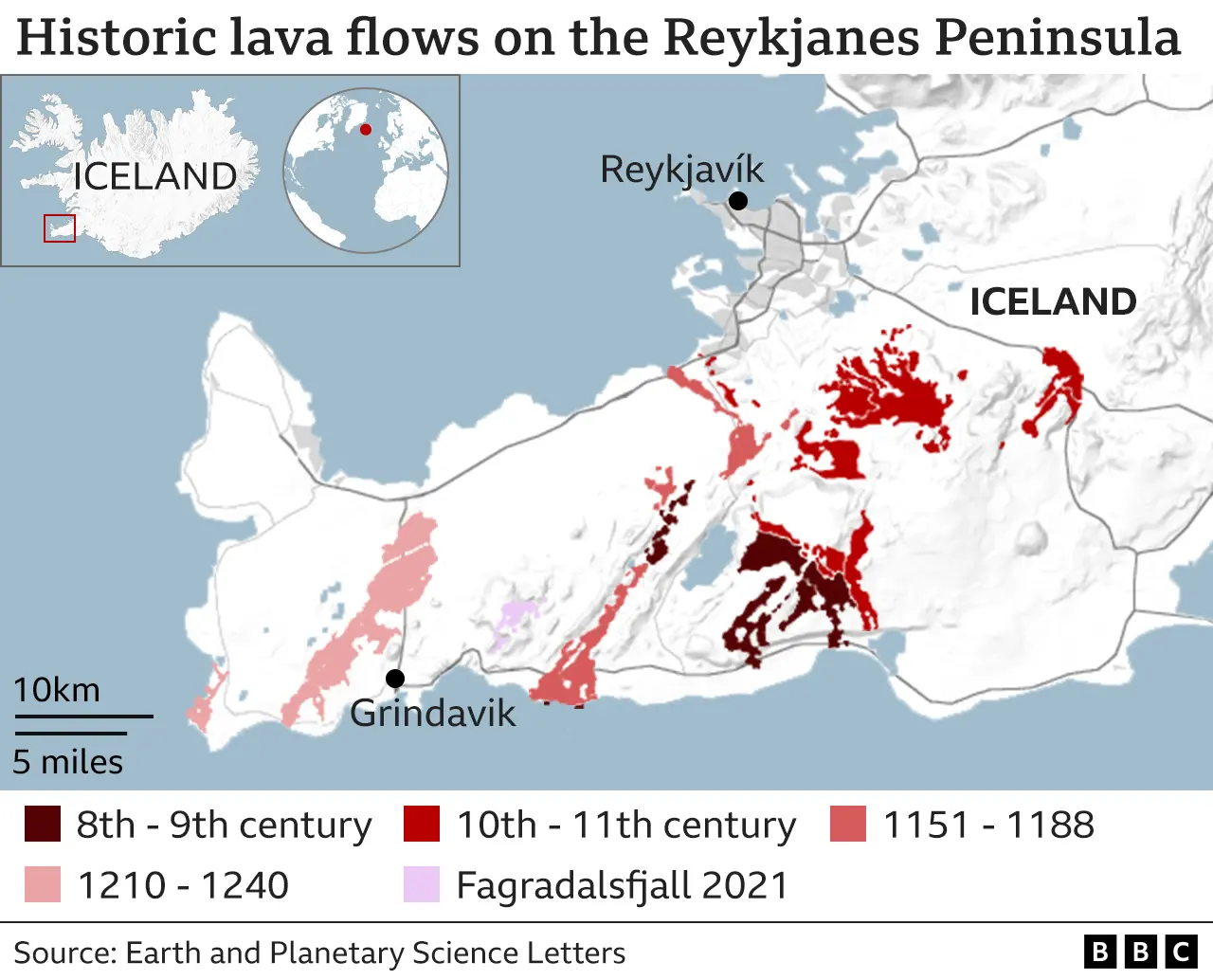

But the last time the Reykjanes Peninsula saw any lava flow was hundreds of years ago, probably starting as early as the 8th or 9th century and continuing until 1240.

Now the eruptions have started again, but why was there an 800-year gap?

“Over geological time, tectonic plates break apart as fast as your fingernails grow, a few centimeters per year,” explains Professor Tamsin Mather, an earth scientist from the University of Oxford.

“But it doesn't seem to be disintegrating smoothly, it's going through these pulses of high activity. And that's probably what we're seeing now in the Reykjane Mountains.”

Rocks in the area can reveal more about the past – showing a pattern of quiet periods lasting about 1,000 years – followed by volcanic eruptions lasting a few centuries.

“There is evidence of about three of these types of events over the past 4,000 years in this region,” Professor Mather explains.

“So this is going as expected at the moment. What we expect is a series of these relatively small, relatively short-lived eruptions over the coming years and decades.”

Getty Images/Copernicus

Getty Images/CopernicusWorking out how to predict when eruptions will occur is a major concern for Iceland at the moment – especially since the city of Grindavik and its geothermal power plant – a key piece of national infrastructure – are in the danger zone.

“Now that eruptions are repeating themselves, scientists have a much better idea of what is happening,” explains Dr. Evgenia Ilinskaya, a volcanologist from the University of Leeds.

“So they've been tracking how the Earth swells as magma emerges from deep within the Earth. Now they can actually know with much greater certainty than previously possible when to expect magma to start penetrating the Earth.”

Reuters

ReutersBut pinpointing exactly where the explosion will occur is more difficult. These are not cone-shaped volcanoes like Mount Etna in Italy, for example, where lava comes out of roughly the same place.

On the Reykjanes Peninsula, magma is held loosely beneath a larger area – and erupts through fissures – or fissures – that can be miles long.

The Icelandic authorities are building large barriers around the city and the power station, which are good at holding back the lava.

But if a crack occurs inside the barriers – as happened in Grindavik in January when some homes were destroyed – not much can be done.

A prolonged period of eruptions would have serious consequences for Iceland.

“This is the most densely populated part of Iceland – so 70% of the population lives within 40 kilometers or so,” explains Dr Ilinskaya.

“And all the major infrastructure is there, like the main international airport, the big geothermal plants, and a lot of the tourism infrastructure as well, which is a big part of Iceland’s economy.”

Major roads being cut off by lava flows and air pollution caused by eruptions are just some of the risks.

Dr. Ilinskaya says the country's capital, Reykjavik, also has the potential to be affected.

“One scenario that could be dangerous for Reykjavik (Iceland’s capital) is for eruptions to move east along the peninsula – there are lava flows from 1,000 years ago from the last eruption cycle that occurred in what is now known as Reykjavik, so based on that, “it’s not “It is not possible for lava flows to flow there in future eruptions.”

Is there a way to predict what will happen in the long term?

Scientists are looking at a number of different volcanic systems found across the peninsula.

“In the last cycle, the first eruptions started in systems to the east and migrated to the west, with some fits and starts here and there,” explains Dr Dave McGarvey of Lancaster University.

This time, the first eruptions – which began in 2021 – occurred in a system located more in the middle of the peninsula.

“It now appears that this system has completely stopped working, and there is no clear indication of magma pooling underneath it. We don't know if that is temporary or if it is something permanent that may never erupt again in this cycle.”

The most recent eruptions, which began in December, are now in an adjacent system a little to the west.

Environmental Protection Agency

Environmental Protection AgencyDr McGarvey says scientists can get an idea of how much magma is underground, and whether it is likely to divert away from Grindavik and the power station into another nearby volcanic system.

“If they see the magma flow rate decreasing, that would be an indicator that it may be starting to stop, and if so it could take a few months for it to completely die down.

“The question then is, is this a temporary lull or is it actually the end of this phase of activity? We are in uncharted territory at that point.”

Scientists are learning more with each eruption, but there is still a great deal of uncertainty for Iceland as a new volcanic era begins.

He follows Rebecca on X (formerly Twitter)

“Travel specialist. Typical social media scholar. Friend of animals everywhere. Freelance zombie ninja. Twitter buff.”

More Stories

Macron rejects left-wing bid to appoint PM before Olympics

Dogs can smell human stress and make decisions accordingly, study says: NPR

Hamas and Fatah sign declaration to form future government as war rages in Gaza