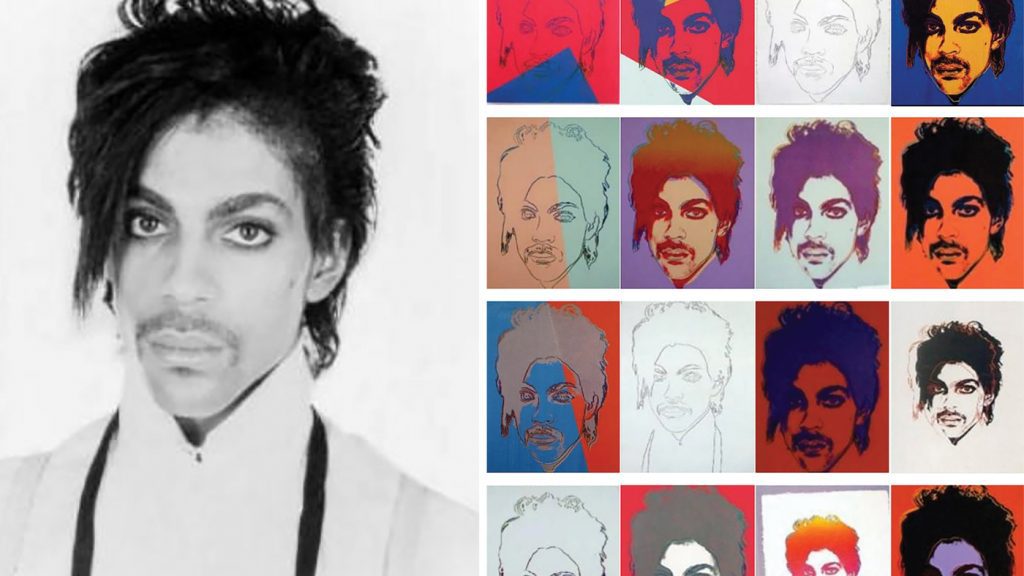

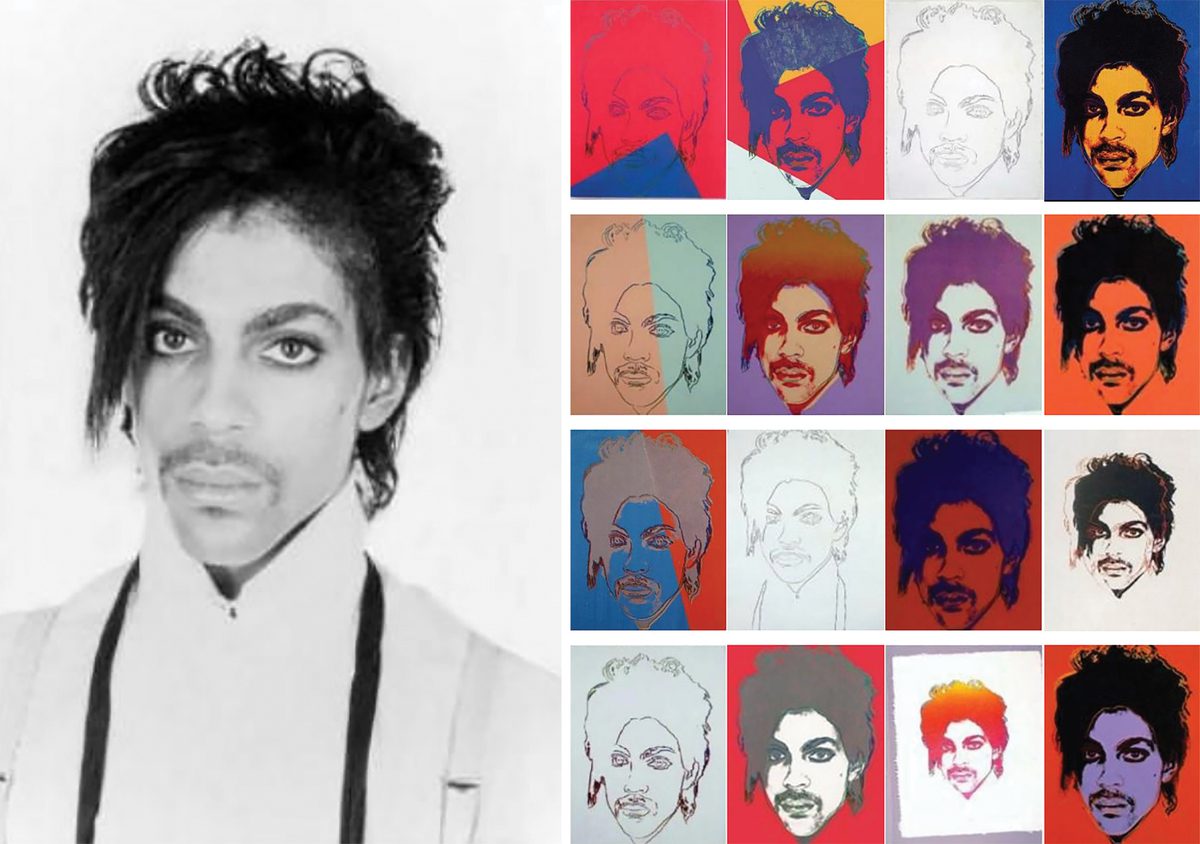

A photograph of the Prince taken by Lynne Goldsmith (left) in 1981 and 16 silkscreen photographs later created by Andy Warhol using the photograph as a reference. A federal district court judge found Warhol’s series to be “transformative” because it conveyed a different message than the original, and thus was a fair use. The Second Court of Appeals Circuit Committee disagreed.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Hide caption

Caption switch

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

A photograph of the Prince taken by Lynne Goldsmith (left) in 1981 and 16 silkscreen photographs later created by Andy Warhol using the photograph as a reference. A federal district court judge found Warhol’s series to be “transformative” because it conveyed a different message than the original, and thus was a fair use. The Second Court of Appeals Circuit Committee disagreed.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Do you know all those famous Andy Warhol’s silkscreen prints of Marilyn Monroe, Liz Taylor, and lots of other stars? Now one of the most famous of the series, the Prince series, is at the center of the case that will be heard by the Supreme Court on Wednesday. It is an issue of great interest to all kinds of artists.

One aspect of the controversy is Lynne Goldsmith, best known for portraying rock stars and working on more than 100 album covers. In 1981, Goldsmith was commissioned to shoot a series of portraits of the Prince NEWSWEEK. At that time, rock star Purple Rain was just starting to take off. Goldsmith photographed him at a concert and invited him to her studio where she gave him purple eyeshadow and lip gloss to accentuate his charisma and masculinity. She even placed her photography umbrellas to create a tingling of light in his eyes. The result was an image that she later said was an image of weakness. NEWSWEEK She did not use the studio photo, opting instead to use the concert photo, and Goldsmith kept the other photos in her files for future publication or licensing.

Three years later, Prince was a star, and Vanity Fair The magazine commissioned Andy Warhol to make an illustration of the Prince for an article she was publishing. When commissioning the work, the magazine asked Warhol to use as a reference point one of Goldsmith’s black and white photographs. The magazine paid Goldsmith $400 in licensing fees and promised in writing to use only the image in this image Vanity Fair the case.

There is no evidence in the record that Warhol was aware of the license agreement. But anyway, he got past it and created a set of 16 Prince’s silkscreens, which he’s copyright to, and one of them Vanity Fair used for the article. The silkscreen images have since been sold and reproduced with hundreds of millions of dollars in profit for the Andy Warhol Foundation, a non-profit organization created after Warhol’s death to promote his work and the visual arts.

After Warhol’s death in 2016, Vanity FairThe parent company, Condé Nast, has accelerated the “Genius of the Prince” tribute, which includes several portraits of the prince, and paid the Warhol Foundation $10,250 to run the “Orange Prince” on its cover. Goldsmith received no payment or credit this time, and eventually sued the foundation, claiming that Warhol had infringed her copyright, and that the foundation owed her millions of dollars in unpaid license fees and royalties.

The foundation responded that Warhol not only copyrighted the famous Prince series, but that his treatment was, legally speaking, “transformative” because his artistic presentation is very different from that of the original Goldsmith. The foundation confirmed that in Warhol’s version, not only did Warhol crop the image to remove the prince’s torso, he resized the image, altered the angle of the prince’s face, altered hues, lighting, and detail, as well as adding layers of vivid color and lighting. Unnatural colours, crisp, hand-drawn outlines, streak screens and stark background shading amplify Prince’s features.

The result, according to the foundation, is a “flat, impersonal, disembodied, mask-like appearance” that is no longer languid but iconic. Essentially, the foundation argues that Warhol used a black and white photograph as a building block, much in the way a collage artist might use slices of different images in a larger work.

As you might imagine, each side has its own experts, and in fact two lower courts differed on this. A federal district court judge found Warhol’s series to be “transformative” because it conveys a different message than the original, and is thus: “fair use” under copyright law. But a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the view, declaring that the judges “should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain … the meaning of the works in question.” If the Supreme Court approves, the Warhol Foundation will have to pay royalties or licensing fees, and possibly other damages to the original creator, Lynne Goldsmith.

Regardless of the Supreme Court’s ruling, its decision will have practical consequences. So it is not surprising that some three dozen Friend’s Court memos has been presented debating one side or the other, representing everyone from the American Publishers Association and the Motion Picture Society of America to the Institute for Library Receivers, the Digital Media Licensing Association, and Dr. The Recording Industry Association of America, and even the union representing NPR Reporters, Editors, and Producers, the Screen Actors Guild of America for Television and Radio Artists.

The result could shift the law into favoring more control by the original artist, but doing so could prevent artists and other content creators who rely on existing work on everything from music and posters to AI creations and documentaries.

“Freelance entrepreneur. Communicator. Gamer. Explorer. Pop culture practitioner.”

More Stories

Francis Ford Coppola talks about kissing in video while filming ‘Megalopolis’

John Mayall, influential blues musician, dies aged 90

Whitmer Promotes The Iron Sheik After Hulk Hogan’s GOP Convention Speech